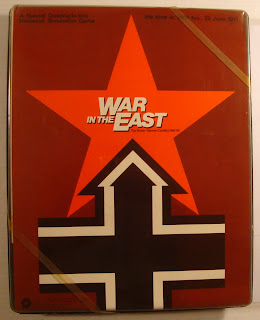

More Recommended Rules Changes for WAR IN THE EAST

INTRODUCTION

In Part I of this essay, I presented several experimental changes to the

WAR IN THE EAST (1st Ed.) rules governing railroad repair units and the formation of battle groups. The purpose of this initial batch of ‘optional’ rules modifications was two-fold: first, to offer players a simple way to increase the standard game’s historical realism; and second, to modify the rules platform in order to create a more challenging and intense gaming experience. Part II of this essay continues where Part I left off by presenting more experimental changes to the standard rules; to whit, a new set of optional rules that modify both the effectiveness and the battlefield mobility of Soviet anti-tank brigades. As was the case with Part I, these changes can be used independently or in combination with some or all of the other procedural modifications presented as part of this project. Readers are again warned, however, that some of these alternative rules — because of their divergence from those found in the standard game — can, and often will, dramatically alter the flow and tempo of

WAR IN THE EAST (1st Ed.); for this reason, those adventuresome players who decide to implement some or all of these rules modifications should proceed with a certain amount of caution.

MORE OPTIONAL RULES CHANGES

3a. Effect of Russian Anti-tank Units on Attacking Axis Mechanized Units (changes to Rules Case 10.5):

The combat strength of Axis mechanized units that participate in an attack against a Soviet-occupied hex containing one or more anti-tank brigades is unaffected by the presence of the anti-tank unit or units. All other modifications (weather, supply, etc.) to the attacking unit or units’ combat strength still apply, but the presence of a Soviet anti-tank brigade in a defending hex NO LONGER HALVES the attack strength of assaulting Axis mechanized units. Instead, Russian anti-tank units have the following effect on combat: whenever Axis mechanized units participate in an attack against a Soviet stack containing one or more anti-tank units, at least half, rounded up, of all of the attacker’s combat losses (whatever the cause: unsupplied attack,

Attacker Exchange,

Exchange,

½ Exchange, etc.) must be extracted in the form of armored or mechanized strength points. The single exception to this rule arises in those cases in which the attacking Axis force does not include sufficient mechanized combat factors to satisfy this loss requirement. Such a situation might occur, for example, if the attacking force possessed no full strength German mechanized divisions but did include mechanized

kampfgruppen or brigade strength units.

3b. Retreat Limitations on Soviet Anti-Tank Units (‘experimental’ changes to Combat Resolution Rules Case 11.0):

Whenever a Russian anti-tank unit is forced to retreat as a direct result of an Axis attack which, after all Axis combat losses have been removed, includes at least one surviving mechanized unit of any size, the anti-tank brigade may not retreat but is eliminated instead. Please note, however, that this rule applies ONLY to anti-tank brigades: all other types of Soviet units required by the Combat Results Table to retreat — whether infantry, cavalry, mechanized, or artillery — are retreated normally.

Rationale:

|

| Soviet anti-tank gun in the Battle of Kursk |

Rules Case 10.5 in

WAR IN THE EAST (1Ed.), which stipulates the “halving” effect of Soviet anti-tank units on attacking Axis mechanized forces, appears — based on my own review of engagements involving German armor versus Russian prepared anti-tank defenses during the first three years of the war — to be significantly at odds with the historical record. Of course, it is difficult to know what Jim Dunnigan actually had in mind when he decided to include Soviet anti-tank units in the

WAR IN THE EAST counter-mix, but their dramatic, if implausible effect on the Axis armor in the game — particularly when viewed in isolation — is significantly greater than was their actual impact on combat on the Eastern Front. Moreover, the astonishing (almost magical) capabilities attributed by the designer to these Soviet units tend to push the players in odd and usually ahistorical directions.

|

| German panzer division moves up to attack, WWII. |

The simulation logic, such as it is, that underpins the standard anti-tank rules seems curious at best, and manipulative at worst. For starters — and for reasons known only to the game designer — the Russian anti-tank counters in

WAR IN THE EAST have been designated as brigades, although historically, these units were usually organized as battalions or, more frequently, as independent regiments. In most cases, these specialized contingents were equipped with 45mm, 57mm (starting in 1942), and 76mm anti-tank guns, often with a smattering of marginally-effective anti-tank rifles and even canine-borne anti-tank mines. That being the case, even if one assumes that each Soviet anti-tank brigade represents two full-strength regiments, their “halving” effect on the attack strength of Axis mechanized units still comes perilously close to pure “Dunniganesque” fantasy. That is to say: there is simply no credible evidence based on a careful review of armor vs. anti-tank engagements on the Russian Front that would support the standard “anti-tank effects” rule as originally written; which, in turn, leads to an obvious question: Since it seems clear that the importance of Soviet anti-tank units has been exaggerated in the published rules for

WAR IN THE EAST, what legitimate role should these specialized units actually play in the game?

|

| German anti-tank gun in the Battle of Stalingrad. |

If we accept history as our guide, the answer necessarily would be a very different one from that envisioned by the game’s designer. Viewed strictly in terms of military doctrine, both the Soviets and the Germans considered the part played by towed anti-tank guns — versus tracked tank-destroyers, for example — as an economical means of channeling and slowing the advance of attacking enemy armor and hence as being highly useful in shaping the battle area. However, neither side considered the battlefield contribution of these mainly static defensive assets to be anywhere near as significant as the critically important role played by Russian anti-tank brigades in the standard game. On the contrary, the Soviet high command (STAVKA) assumed that an anti-tank regiment which had been deployed on suitable terrain and in prepared positions — that is: layered, interlocking defensive zones that included tank obstacles, pre-fabricated concrete block bunkers, and camouflaged, reinforced dugouts — AND WHICH WAS ALSO BACKED UP BY ARTILLERY, should be able to disable between two and three dozen enemy tanks before the regiment either defeated the German assault or was overrun by the attacking enemy force. It should be noted that this number could be higher, but usually only if the local terrain was especially well-suited to the defense. Hence, based on their experiences during the early defensive engagements around Moscow and Leningrad, Red Army commanders seem to have decided that, given optimal battlefield conditions, a well-sited anti-tank regiment should be able to both slow and blunt even a determined German armored assault before such a regiment was, itself, destroyed in place. In short, the battlefield effectiveness of Soviet anti-tank units against enemy armor, while not viewed as being decisive, was still considered to be well worth their investment in men and materiel. Needless-to-say, the loss (even if temporary) of forty-eight to seventy-two tanks — the projected casualties from amongst enemy armored vehicles inflicted by two properly supported Soviet anti-tank regiments — would be a nontrivial price for an Axis assaulting force to pay. Nonetheless, armored losses on this scale typically would not, contrary to the

WAR IN THE EAST standard rules, utterly degrade the offensive capabilities of an attacking panzer corps, and most certainly would not significantly reduce the striking power of an entire panzer army.

|

| German Tiger destroys Soviet T34 at Kursk |

Probably the most pernicious (and frustrating) effect of the “anti-tank” effects rule — at least in the case of the

Campaign Game — is that, after the first few invasion game turns, it makes the printed combat strength of the German mechanized divisions largely irrelevant to Axis offensive play. Instead, what this rule really does is to magnify the utility and combat value of non-motorized German “leg” infantry divisions when they are used to attack Russian prepared positions. Moreover, for all of the Soviet anti-tank brigades’ inflated defensive power, these units, curiously enough, really do not fulfill the one function in the standard game that they actually did serve on the Russian battlefield; that is: to attrite the

Wehrmacht’s mechanized strength by destroying or disabling German armored vehicles. Thus, for much of the

WAR IN THE EAST Campaign Game, combat losses from amongst the mechanized forces of the two belligerents will usually be disconcertingly low. In fact, both sides will tend to suffer the greater part of their armored casualties when their mechanized units are defending against, rather than attacking the enemy. This means that — for a large part of the game — the mechanized forces available to both sides will tend to be much stronger than was the case historically. Furthermore, despite the fact that this game dynamic is unrealistic,nonetheless, it is the inevitable result of a combat system in which the losses incurred by both the Germans and the Russians when attacking will, with very few exceptions, be extracted from participating infantry units rather than from the mechanized forces directly involved in the battle.

And that's not all: there is another irksome problem with the designer’s somewhat mystical approach to Soviet anti-tank units in

WAR IN THE EAST that warrants attention: Dunnigan treats all of these brigades, at least for movement purposes, as being motorized. To be fair, it is true that a certain percentage of the Red Army’s anti-tank regiments were assigned their own organic motor transport; however, from my own reading of the historical record, it appears that a substantial number, if not the majority of these specialized units, depended on horses for their mobility, particularly during the first three years of the war. This factor, when considered along with the standard Soviet practice of aggressive forward deployment of their anti-tank assets, made any kind of organized withdrawal in the face of a powerful enemy armored attack — particularly one supported by air power — exceedingly difficult, if not almost impossible. Individual gunners might escape to fight another day, but the anti-tank guns — whether pulled by horses or by trucks — were most unlikely to survive a retreat across a battlefield dominated by roving enemy armor.

Probable Effects of Recommended Rules Change 3a:

Substituting the optional (3a) rules case for the standard Soviet “armored effects” rule, as might be expected given the preceding commentary, will fundamentally alter certain key aspects of play in

WAR IN THE EAST. For example, players who opt to use the experimental Russian anti-tank rule instead of the regular “halving” version will quickly discover that traditional German and Soviet tactical formulas — beginning with the initial invasion game turns — are more problematical than in the regular game; moreover, adopting this procedural change will also noticeably increase battlefield attrition for both belligerents. One reason for this result, of course, is that incorporating this rules modification into the game significantly enhances the offensive hitting-power of the German mechanized forces, especially during the first few years of the war when the

Wehrmacht is still ascendant; in addition, besides improving Axis offensive prospects, it also encourages the Soviets to expand the defensive role of their own mechanized units, as well. Perhaps, most importantly, this change operates to realistically redirect the general flow and tempo of the Campaign Game; and for this reason, it tends to produce — in my opinion, at least — a more historically satisfying model of mobile warfare on the Russian Front. Moreover, my reasons for recommending this rules change will, I believe, become apparent as soon as the very different battlefield effects of the standard and modified versions of the anti-tank rules are compared.

|

| Trench warfare at Leningrad. |

The first and most obvious effect on play of the (3a) experimental rules option, as noted earlier, is that it restores the offensive power of the German mechanized arm

vis-à-vis virtually any Soviet defensive system that can conceivably be arrayed against it. Of course, it goes without saying that the specific defensive arrangements deployed by the Soviet high command will oftentimes vary across different sections of the game map and these variations will inevitably be influenced by the following factors: the local availability of Soviet rifle strength; the proximity to the frontline of important Axis objectives (i.e., major Russian population centers); the presence or absence of advantageous defensive terrain; and the season of the year. However, even when taking all of these different factors into consideration, the “backbone” of the typical Russian defense — at least when using the regular (printed) anti-tank “armored effects” rule — will still be the multi-layered, easy-to-construct, and economical-to-build “fortified” line. Not surprisingly, using the (3a) change to the anti-tank rules noticeably reduces the effectiveness of this popular Soviet approach, particularly during the critical first two years of the war. If this is indeed the case, and I believe that it is, then it probably makes sense — before moving on to the specific effects on play of the proposed rules change — to briefly revisit the tactics used by both sides when the standard anti-tank rules are in force. To that end, what follows next is a brief analysis of the dominant patterns of offensive and defensive play that shape the flow of a regular game of

WAR IN THE EAST, with special attention given to the German summer campaign seasons of 1941, 1942, and 1943.

|

| Battle for Moscow, Soviet Siberian soldiers. |

Of course, a number of major engagements in Russia did not occur in summer: the Battle for Moscow (1941-42); the Battle of Rzhev (1942); the Stalingrad Encirclement (1942-43); Manstein’s “Backhand Blow” (1943), to name only a few. And true to the historical record,

WAR IN THE EAST has been designed so that the Red Army will largely control the offensive tempo of the game during each and every fall, winter, and spring beginning with the first fall and winter of the war. However, during the summer months of 1941 and 1942, and to a lesser extent, 1943, the game’s basic architecture shifts the offensive advantage back in favor of the Germans. This means that, although the winter battles are important when it comes to furthering Russia’s long-term prospects for victory, the game will, in most cases, actually be won or lost depending on the outcomes of the Axis summer campaigns of 1941 and 42. Thus, the main goal of the Soviet high command, particularly during these critical early years, will be to establish and maintain a defensive posture that can successfully withstand the offensive power of the Germans during that portion of the game when the Axis forces are at their strongest.

|

| Russian soldiers and train. |

When it comes down to the actual “nitty-gritty” of play, the most widely-used defensive strategy employed by the Soviets in the standard game — for those readers who are unfamiliar with

WAR IN THE EAST — is one that relies on a contiguous line of hexes (preferably as straight as possible) each of which is occupied by a fortified infantry division, a Guards rifle corps (if available), and an anti-tank brigade. This popular linear configuration forms the foundation for the Red Army’s defensive strategy because it guarantees that, in order to capture a Soviet-controlled frontline hex, the attacking Axis divisions must overcome a perfectly-balanced Russian force that possesses a defensive combat strength of 14 factors and an exchange value of 9 factors. Moreover, to insure that the Germans do not achieve a sudden, unexpected breakthrough, the Soviets will virtually always deploy several (two to four) additional belts of static 0-3-0 fortified units (converted 1-4 infantry divisions) immediately behind this first line of continuous strong-points; these, in turn, will typically be backed-up by reserve units of varying types, all of which are close enough to move into the gaps that will inevitably appear either as the frontline lengthens, or as defending Russian units are eliminated in combat. Clearly then, this Soviet defensive strategy — at least when playing using the standard anti-tank rules — presents a formidable barrier to any German advance: the Axis cannot achieve better than 3 to 1 odds against such a prepared position from two hexes and only 5 to 1 (at best) from three hexes. Moreover, this baked-in Soviet ability to restrict Axis battle odds in the standard game is especially critical because, even when using CRT #1 (the most advantageous to the attacker of the game’s four Combat Results Tables), the best combat result (attrition-wise) that the attacker can hope to gain — even at odds of 5 to 1 — is a

½ Exchange. What is even more potentially troublesome to the assaulting Germans is that most of their attacks will have to be conducted at odds of 3 to 1. And battles fought at 3 to 1, with or without friendly air support, offer the attacker no prospect at all of generating an

Exchange or

½ Exchange, but, nonetheless, still carry an appreciable risk of the “dreaded”

Attacker Exchange result: a combat outcome that requires the attacker to lose factors equal to the face value of the defender’s combat strength, but leaves the defending units in the target hex unaffected.

|

| Soviet 76mm anti-tank artillery |

In game terms, this means that Dunnigan’s anti-tank rules virtually guarantee that, after the initial massacre of Soviet frontier forces in June-July 1941, the

Wehrmacht’s summer offensives of late 1941 and 1942 will, with very few exceptions, take the shape of extended and bloody, set-piece “slugging matches.” This pattern of play, although it is an inescapable feature of the standard game’s design, is problematical because, historically-speaking, the first protracted set-piece German action of this sort did not actually occur in Russia until Hitler’s failed "Zitadelle" offensive at Kursk in July, 1943. Thus, despite the fact that these types of costly, static engagements seriously undermine the German Army’s strategic goal of conservation of forces, the game’s victory conditions require the Axis to attack (regardless of casualties) during the first few summers of the war. For this reason and in spite of the

Wehrmacht’s stacking and early-game CRT advantages, the heavy losses caused by these bloody attrition battles will almost always operate to damage the Germans’ long-term prospects for victory, should the game continue much past the summer of 1943. In short, the German side will have good reason be worried about their steadily accumulating casualties during these largely unavoidable slugging matches, while the Russian view of these bloody summer clashes will typically tend to be a bit more positive. This is because, as these protracted summer battles grind on, the Soviets will typically suffer significantly fewer casualties from among their high value units than will their Axis adversaries; and what losses the Red Army’s forces do suffer will mainly come from their static (fortified) infantry divisions, thanks to the commonly-used Soviet tactic of evacuating units from an exposed position as soon as it can be attacked from three or more hexes (leaving the immobile 0-3-0 behind, of course, to serve as a rear guard).

|

| Soviet howitzers at the Battle of Kursk |

Based on my description, thus far, of the tactics most likely to be used in the standard game, it might appear that

WAR IN THE EAST players should not expect to see the main effects of the recommended (3a) change to the anti-tank rules until the set-piece defensive engagements of 1941-1943; it turns out, however, that such is really not the case. Incorporating the new, “weaker” version of the anti-tank rules directly undercuts the usefulness of traditional Soviet defensive tactics both during the short

Barbarossa Scenario (20 game turns) and also during the early “frontier battles” phase of the

Campaign Game (208 turns) by significantly reducing the frontline Russian anti-tank brigades’ ability to impede the advance of the German mechanized forces in the critical first weeks of the Axis invasion. Why and how this change occurs actually derives from two very different features of the

WAR IN THE EAST KURSK-based game system: the first is the threat of encirclement posed by enemy mechanized breakthroughs and exploitation movement; the second is the powerful effect of (unfrozen) river lines on combat. Both game elements are important, so let us briefly examine how the anti-tank rules interact with this pair of design features when it comes to the actual play of the game.

|

| Soviet machinegun crew |

Any player who has tried one of the many titles based on the

KURSK Game System will know that, because of the ability of mechanized units to move both before and after the combat phase, a defense — if it is to be successful — requires the establishment of a second line of units and/or zones of control (ZOCs) behind the defender’s initial line of resistance. The creation of such an impenetrable secondary barrier serves to prevent exploiting mechanized units from passing through any gaps suddenly opened in the non-phasing player’s front as a result of losses incurred during the immediately preceding combat phase; needless-to-say, this “double-line” defensive approach is critical because exploiting mechanized units, if left unimpeded, can slice deep into the non-phasing player’s rear areas to cut supply lines or to encircle exposed sections of the defender’s front. In the case of

WAR IN THE EAST, this problem is further complicated by the fact that the rules require that, prior to the start of the game, a sizeable part of the Red Army be set up adjacent to or within a few hexes of the Axis-Soviet frontier; hence, the establishment of a second defensive line is absolutely essential if the Russians are to prevent the bulk of their frontline units from being encircled on the first and second turns of the

Barbarossa Scenario or the

Campaign Game. To make matters worse, the defender’s second line must be uniformly strong enough to prevent enemy mechanized units from overrunning any part of it during exploitation movement. And because of stacking limitations on overrunning units (only three attacking units may participate in the same overrun), a total of three combat factors per hex is typically required to prevent stacks of enemy armor from rolling over a defender’s position during either the initial or the mechanized movement phases. However, when using the game designer’s original anti-tank rules, a single Soviet anti-tank unit behind a river or, alternatively, an anti-tank brigade stacked in the open with an infantry or cavalry division (a total of only two defense factors) is sufficient to make the target hex immune to an Axis mechanized overrun because of the “halving” effect that the anti-tank unit has on enemy armor.

|

| Germans advance at Kursk, July 1943 |

Unfortunately for the Russians, this all changes when the (3a) rules modification is substituted for Dunnigan’s original version of the anti-tank rules. Instead, with the new “weaker” rule in place, a Soviet anti-tank brigade — putting aside, for a moment, its 10-hex movement range — becomes no more useful in preventing German overruns than any other (one defense value) unit in the Russian counter-mix. This is no trivial matter, particularly in the north and south sections of the front where — unlike the center — there are fewer forest or swamp hexes on the map to block enemy mechanized ZOCs. Thus, until the Russian forces that were lucky enough to escape the first turn carnage near the Axis-Soviet border can withdraw beyond the reach of a supplied German army, the combination of enemy ZOCs to the front and air interdiction markers in the rear will make it very difficult for the Red Army to extricate many of its less mobile units — particularly its 1-4 rifle and 1-3 cavalry divisions — from the lethal clutches of the onrushing

Wehrmacht. To this set of concerns, the Russians can also add another worry; that is: when playing with the post-publication (official SPI

errata as of Sept. ’74) “Arms Center Disruption” rule — which stipulates that all on-map arms centers must cease production as soon as the Soviets lose 100 or more units (of any flavor) and may not resume producing arms points until game turn 21 — the increased exposure of Russian units, brought about by this rules change, can often mean that the 100 unit “arms disruption” threshold will be crossed one or even two turns earlier than in the standard game; this represents an increased loss to the Soviets of typically between 20 and 40+ badly-needed arms points.

|

Soviet women dig anti-tank ditch in front of

Leningrad, Summer, 1941. |

Moreover, to add insult to injury for the Soviets, it turns out that besides making a successful Russian withdrawal vastly more complicated during the early post-invasion game turns, the substitution of the experimental (3a) rules change also makes it much more difficult to slow or block the initial advance of German mechanized forces in the north and center. The reasons for this are several, but the most important has to do with the initial role of the German infantry. Once the

Barbarossa or

Campaign Games begin, most of the

Wehrmacht’s non-mechanized units will be tasked with liquidating the inevitable scattered pockets of Soviet units that survived the opening Axis attacks but which were unable to escape to the east; hence, Hitler’s panzers will initially be obliged to strike off in pursuit of the fleeing Russians with little or no infantry support. This common early-game dynamic, when playing with the original anti-tank rules, makes it possible for the Red Army to slow or even temporarily halt supplied German mechanized forces in the north and center using a combination of armor, anti-tank units, and river lines. Interestingly, the successful application of this Soviet approach actually depends on several different game elements, but German stacking limits are really the most important contributor to its effectiveness. In

WAR IN THE EAST, the most powerful force that the Germans can concentrate in one hex is four 10-8 panzer divisions, for a total of forty attack factors; this is a force that the Soviets cannot hope to match in the early turns of the game. However, an easy-to-muster Russian stack composed of a 2-5 tank brigade, a 3-5 tank brigade, and a 0-1-10 anti-tank brigade (a total of six printed defense factors) — even if in the open — presents an attacking German mechanized force with an effective defense strength of twelve factors; more importantly, the same Soviet stack defending against an unsupplied German mechanized force or deployed behind a river is equivalent to twenty-four very intimidating (and 4 to 1 proof) defense factors. This is because the attack strength of the panzers and panzer grenadiers, in every one of these examples, is halved (in some cases, multiple times) before combat is resolved. In game terms, this means that the Russians can use this tactic to slow the progress of both Army Group Center’s and Army Group North’s mechanized units when it matters most. And because even the gain of a few extra turns of delay can buy enough time for arriving Russian reinforcements to fortify much, if not all, of the ground in front of both Moscow and Leningrad, this rule seriously impacts the Red Army’s defensive options during the critical summer game turns of 1941.

|

| Soviet POWs under German guard, sumer 1941 |

What all this means is that, whether viewed in the context of the initial frontier battles of summer 1941, or with an eye towards the wider impact of this (3a) rules change during the first few years of the war, Russian losses (along with those of the German mechanized arm) will inevitably increase, and increase substantially. The other notable effect of this rules modification is that it, at least partially, restores the importance of terrain in shaping the battle area: river lines, especially, become much more important to the Russians when the anti-tank ‘halving’ rule is discarded and replaced by its “weaker” alternative. Stated differently: the halving effect of rivers — at least when it comes to Soviet defensive play — will, in most cases, become a more important defensive consideration for the Russians than limiting the number of hexes available to the attacker. Thus, the “ruler-straight” and “snake dance” Soviet defensive configurations that regularly appear in the standard game will tend — as a direct result of this rules change — to give way to the more meandering frontlines that actually characterized the historical campaign.

Last but not least, of course, is the increased attrition that this change will introduce into the dynamic of the

WAR IN THE EAST game system. Simply stated, the Soviets will, because of this change, suffer much higher losses among their “high value” units than in the standard game; however, just as importantly, the Germans will also be forced to accept significantly higher casualties among their mechanized forces if they choose, as they almost certainly will, to commit their panzer and panzer grenadier divisions to high-odds assaults against the Russian line. Thus, this rules change will tend to produce — typically, by early 1942 — a battlefield environment in which the orders of battle of the two opposing armies will be both weaker and more brittle than in the standard game.

Probable Effects of Recommended Rules Change 3b:

In the standard game of

WAR IN THE EAST, the Soviet side usually constructs about forty-five to fifty anti-tank brigades during the first months of the war, and then never builds another one of these units for the rest of the game. This, in its own way, is just as ridiculously unrealistic, from a historical standpoint, as the already-railed against, but nonetheless typical game phenomenon of German panzer divisions operating for much of the war without (figuratively speaking) ever suffering so much as a scratch as a result of combat operations.

|

| Soviet WWII tank production factory |

The adoption of the 3b rules change will, like its 3a “cousin,” affect the trajectory of the game (particularly, the Campaign version) in several important ways. First, it creates a battlefield role, albeit a small one, for the otherwise largely useless Axis allied mechanized units. The second but most immediate effect of this change, not surprisingly, will be to dramatically increase losses among Russian anti-tank units. This, in turn, will mean that the Soviets, if they wish to maintain a reservoir of these “weakened” but still useful brigades, will have to devote a fairly significant number of arms points to their construction for at least the first two to two-and-a-half years of the war. In terms of Soviet force levels, both in the short and in the long term, this is an important change. In the short term, it means that more Soviet Production capacity (Training Center tracks), along with more personnel and arms points, will have to be directed towards the construction of anti-tank brigades, particularly during the summers of 1941 and 42. Long term, of course, the diversion of increased numbers of scarce Production resources towards the construction of purely defensive units means, in turn, that the Russians will not be able to construct as many of the expensive (especially, in arms points) offensive units as they would otherwise be able to produce in the standard game. In short, both 1942 and 1943, because of the 3b rules change will tend to see a Soviet combat force with fewer tank corps, artillery corps, or air units than would typically be the case. The end result of this change therefore will often be a situation, particularly during the summer of 1942, in which the Soviet position is much more precarious than in the standard game: a strategic situation, in short, in which an Axis decisive victory is still possible, even in this, the second year of the war.

CONCLUSION

More Recommended WAR IN THE EAST Rules Changes are Coming Soon:

|

| Soviet Anti-tank Hunters with mine dogs |

This essay is the second of several that will propose a collection of — in my opinion, at least — challenging and historically-grounded changes to the standard rules for the first edition of

WAR IN THE EAST. My goal, in presenting these rules alternatives, as I indicated earlier, is to rekindle a little interest in this great old title, and perhaps, to spur a few players to do a little experimenting with the game on their own. That being said, Part III of this series will — when I get around to publishing it — offer yet a few more recommended changes to the standard

WIE Campaign Game rules that, hopefully, will compliment those presented here. Of course you can’t please everyone, so for those readers who don’t like any of the recommendations that I have put forward thus far, I urge them to do a little rules tinkering on their own. While it is rarely worthwhile to radically alter a simulation’s basic design architecture, sometimes one or two small tweaks can have a very pleasing effect on a game and its playability. And when looking for rules inspiration, the historical record is almost always a great source for new ideas.

Finally, for those players who prefer to leave the ‘rules writing’ to others, I want to repeat my earlier warning: some of the rules modifications recommended in this set of essays have been tested fairly extensively, but some have not (much like most commercially-produced games). For this reason, those readers who are tempted to actually experiment with one or both of the above optional rules are urged to proceed with caution; some of the changes that have been recommended in Part I, as already noted, will have only a modest effect on the game, but the two listed in this installment have the potential to affect play and play-balance significantly. Consider this “a word to the wise.”

Excellent, excellent rules revision and--perhaps more importantly--accompanying analysis, Joe. I can only hope the folks over at Decision Games who aim to revise WAR IN EUROPE (and the component WAR IN THE EAST game contained within) incorporate your rules revisions into their playtesting efforts!

Greetings Eric:

As always, thank you for your kind words.

I guess -- just like Chuck Sutherland -- I cannot quite bring myself to give up on this game. Despite the many titles that have come after it, I still like both WAR IN THE EAST and DNO/UNT, but -- putting aside my own personal preferences -- I have to admit that DNO/UNT (or FIRE IN THE EAST, etc., etc.) simply isn't as accessible to inexperienced players as is Dunnigan's first "monster" game, even with its many flaws.

And I'm sorry, but "block" or "point-to-point" treatments of this campaign -- no matter how visually attractive or well realized -- simply don't work for me. So, I guess that I will continue to wait for Decision Games or some other publisher to finally combine the best elements of several different game systems into the perfect (hex and counter) treatment of "The Great patriotic War."

Best Regards, Joe

Good job, Joe. I personally believe the whole AT unit thing was a kludge put in after the fact to offset the ahistorically low combat ratings of the Soviet Army vis-a-vis the Germans. Especially in 1941, there were many Soviet rifle divisions that rated considerably higher than a "1" in combat value, and, while those values tended to drop over time (due mostly to low manning numbers), even so a "1-4" standard rifle division is too weak to compete effectively with the German Army. Had more realistic combat values been chosen from the beginning, and something along the lines of a "National Morale" rule been utilized as a combat modifier vice the multiple CRTs, I suspect you would have a much more historically-flowing game process than is currently the case. Anyway, I find your analysis trenchant and accurate and well worth publicizing to Ty Bomba and the crew as they work on the latest version of War in Europe. Whether anything would come of that, I don't know, but at least it provides a valuable set of facts and arguments against continuing to perpetrate the "great Anti-Tank unit fraud" on an unsuspecting gaming community!

v/r

Jeff

Greetings Jeff:

Thanks for visiting.

It is interesting that you mention Frank Davis' concept of "National Morale" in the context of 'WAR IN THE EAST'. In point of fact, I discussed that very same idea with Eric Walters quite some time back. Like you, I really think that tying military capabilities to the battlefield fortunes (among other things) of the two belligerents would offer a big improvement over Dunnigan's original (and quite arbitrary) four tables approach to combat resolution.

As you note, if Decision Games is actually going to go to the trouble of reworking the whole 'WAR IN EUROPE' franchise, the least that they could do is make a few improvments tp what is otherwise a thirty-five year old design. Don't get me wrong, I still like (and own) the original "flatpack" game; but given what we know now, it could certainly be umproved upon.

Best Regards, Joe

Nice blog JB, excellent reading (semble Part 1).

Also agree with Jeff Vandines' concept:

"Had more realistic combat values been chosen from the beginning, and something along the lines of a "National Morale" rule been utilized as a combat modifier vice the multiple CRTs, I suspect you would have a much more historically-flowing game process than is currently the case."

Something I think we have already discussed on another forum, vis a vis the Soviet combat values in PGG, Kharkov, DOS and the AGS quad in comparative terms.

Always worried though that if you tweak up too many bits of JFD's DFE construct you might push things too far in one direction or another.

Anyway, what thoughts have you (if any) about upgrading any revision to PGG mechanics, with panzer corps/ tank army integrity uplifts, all odds overruns, etc? Probably needs to be connected with an uplift in Soviet strengths across the board, and an increase in capacity to produce the many more divisions (and brigades) that were historically fielded and 'expended'?

Perhaps this is a subject for its own blog?

PS

Being a grumpy old bloke and not willing to clog up my system with google chrome scripts, 'atom' (whatever that is) and suchlike, is there some way to subscribe to comments by getting an oldfashioned email notification?

Greetings Ian R:

Thank you for your kind words.

Regarding 'WItE', I am inclined to think that Dunnigan -- having (I am sure) at least looked at GDW's 'DRANG NACH OSTEN' -- decided on the simple design trick of making Soviet divisions 1-4s in order to prevent the Red Army from counter-punching during the summer '41 campaign season. This conclusion makes sense to me because one of the interesting (and pleasing) characterisitics of 'DNO' is the unexpected lethality of the Soviet armored forces thanks to the game's "armored effects" rules. I and my fellow 'DNO/UNT' players noticed almost immediately that initiative was absolutely critical to the opening phases of the game; and that, if the Soviets were allowed to move and attack first on the June II '41 game turn, then all of those seemingly "weak" Soviet tank brigades would be able to inflict horrific damage on the German forces marshalled along the Russo-Axis frontier.

Moreover, I also think that Dunnigan wanted to avoid another peculiar characteristic of the earlier GDW East Front game; that is: the tendency for large swaths of "no-mans land" to form between the two opposing armies because of the significant advantage given to the attacker by the combat system.

Thus, for these reasons and others, I believe that many of the rules and OoB decisions that Jimmy finally settled on were almost completely "outcomes-based". That is: he wanted lots of Soviet formations to be destroyed in the early going, and he wanted the '41 summer campaign to end up with frontlines that vaguely, at least, matched those of the historical campaign. That being said, I have a strong suspicion that Dunnigan was worried that if the Russians began the game with stronger (corps-sized) combat units, then the Wehrmacht would have a very difficult time making the kind of dramatic gains that they actually did in the first months of "Barbarossa". Finally, I really think that Dunnigan also wanted to avoid the "no-man's-land" anomaly that had turned out to be such a serious and virtually unfixable defect in 'DNO'; in its place, I believe he decided that, whatever it took, the opposing armies in 'WItE' -- as was the case historically -- were going to end up holding positions that were literally nose-to-nose along the entire width of the Russian Front.

Regarding the second issue that you raise, the questions of how and where to tweak the 'PGG' Game System is an interesting one. As you note, it is a very easy game system to criticize, but a very difficult one to modify without causing it to "blow-up" in one's face! Obviously, one possible simple approach would be to borrow a few ideas from 'KHARKOV'; that is: to add extra steps for some of the larger Soviet units along with some sort of a "disengagement" rule so that at least some units adjacent to the enemy could break contact. However, besides than these relatively modest adjustments, I hesitate to recommend other more radical changes. My own experience has been that the "rule of unexpected consequences" has tended to show up with alarming regularity whenever I and my friends have decided to try "home-brewed" rules modifications to PGG or its many cousins, no matter how reasonable they appeared prior to play. Moreover, 'PGG-based' games like 'FULDA GAP' really don't seem to offer much when it comes to workable rules changes for the WW II games, either. Obviously, the addition of more and different combat units is (for me, at least) almost always appealing, but I suspect that the end result would probably be to seriously bog down action in the game for both players.

Well, I've rambled on long enough ...

Thanks again for your thoughtful comments and

Best Regards, Joe

Greetings Again Ian R:

I apologize for the somewhat disjointed organization of my previous comments: I inadvertently exceeded the number of characters allowed by "Blogger" so I ended up having to delete whole paragraphs in order to get my host site to allow me to post.

That being said, I think that there are undoubtedly any number of good ideas that might be incorporated into the 'PGG' Game System; the problem, of course, is (as it usually is) adequately play-testing them. I can, for example, see how it might be beneficial to allow Russian armored and mechanized divisions from the same army to benefit from a "corps" attack strength multiplier similar to the German mechanized "divisional" multiplier. However, what such a change would actually do to the game, I have no idea. Changes in the number and types of air missions might also be interesting. This is certainly something that I have toyed with, at various times.

Unfortunately, this type of rules project can often be more trouble than it is worth unless it is undertaken by a dedicated group of gamers who are prepared to see it through. I and my friends were prepared to take on just such a challenge in the case of DNO/UNT, but, that was a long, long time ago. Given the proliferation of new games pouring into the contemporary market, I'm not really sure that it would be possible to find a group fanatically-devoted enough to a single game that they would be willing to take on such a project, nowadays.

Finally, regarding your question about "emailing" comments, I will have to take it up with my wife when she gets home; I just write this stuff, she's the "computer person" in the family.

Thanks again for sharing your ideas and

Best Regards, Joe

Greetings Ian R:

If you do not want to use an RSS Feed reader or your web browser to receive RSS feed notices of posts or comments, you CAN do so in SOME email applications, such as MS Outlook 2007. Then you receive the feed like regular emails. After you have subscribed to RSS in Outlook 2007, a folder is displayed for the new RSS Feed in the Navigation Pane. When you open the folder, the latest items downloaded from the RSS Feed are displayed.

Outlook checks the RSS publisher's server for new and updated items on a regular schedule.

The new and updated items are downloaded to Outlook and displayed in the folder for that RSS Feed. You open, read, and delete these RSS items just as you would any mail message. You can even move, flag, or forward the items to someone else.

I hope this helps.

Also, if you want to subscribe by EMAIL to just the comments on a particular Map and Counters post like this one, you can post a comment and before you hit "Post Comment", choose "Subscribe by email". The email address you use in Blogger to comment will receive notices of subsequent comments.

Best Regards, Barbara

Greetings Again Ian R:

I'm sorry to have taken so long to get to the real meat of your comments, but I have been trying to track down a file that I could post as part of this follow-up note; unfortunately, I'm still looking so it appears that it will have to go up later.

The issue -- which you allude to -- of attempting to graft the 'PGG' Game System onto 'WItE' has already been tackled by Chuck Sutherland in his very detailed 'WItE' Variant: "PANZERGRUPPE GUDERIAN meets WAR IN THE EAST: Attack on the March". It was this file that I was looking for, but have, thus far, been unable to track down.

In any case, Chuck's suggestions are much more radical than mine and, although we disagree (strongly) on some aspects of his "rules fixes", we, nonetheless, see eye-to-eye on a number of others. The biggest problem that I personally have (fairly or unfairly) with Chuck's approach is that it seems to be mainly aimed at defeating Oktay Oztunali's "Quick-Step" strategy. And to this end, the supply rules and ZOC rules are modified significantly. Needless-to-say, allowing the Germans to attack the Russians throughout the summer of '41 (as Chuck's variant does) also means that the Soviet production rules have to liberalized considerably to make up for the much higher casualties that the Russians inevitably suffer. Obviously, I don't like everything about the "Attack on the March" rules changes, but there are enough interesting ideas contained in them to make it worth your while to check out.

In the meantime, I will try to find the time to track down a link: I'm pretty sure Chuck posted something both at Boardgamegeek and over at the CSW WItE forum. When I get an opportunity, I'll check both. However, if you stumble on a link before I do, please let me know!

Best Regards, Joe

Actually the lack of real supply rules is biggest problem with DNO and WIE. Most of WWI-WWII division’s offensive combat power came from its artillery, and artillery ammunition is very difficult to transport pass the railhead. The real strength of the Panzer division was all their trucks not their Mk IIs and IIIs. It was the loss of trucks that degraded German Offensive capability and lend lease vehicles that built of the Russian capability as much as changes in equipment and doctrine. The supply system from “Winter Storm” is good example of what is needed. An attack supply (aka AH Battle of the Bulge) where 90% of counters move at horse drawn rate and a few move at truck rate could work too. You could take it a step further and add depot counters that allow a fix number of Supply chits to be placed on them per turn but would take several turns to relocate (and only to rail line or port). The German supply of chits would decrease with time while the Russians supply would increase. The x-hexes from a railroad and you have unlimited supply is going to require distortion in the rest of game system to limit offensive capabilities to a somewhat realistic level be super anti-tank units or no mans land.

Greetings Tom:

You are quite correct that motorized transport was the key to mobile operations during World War II and that the German infantry division of 1941 was little changed from that of 1916.

One concept that I toyed with, as a means of rationalizing offensive operations in both WItE and in DNO/UNT, was to incorporate elements from the supply and combat systems of PANZERARMEE AFRIKA; that is: truck units, immobile supply counters, and various levels of "attack supply" depending on how close the supply counter was to the front, and whether or not it was expended to support the attack. The idea of an attacking force without surplus mototized assets -- in this case trucks -- having to balance its supply requirements against mobility strikes me as both useful and realistic. Such a modified system, it strikes me, would require little more than an adjustment in the two belligerents' inventories of spare truck units and supply counters to pretty effectively control the numbers and locations of attacks.

Needless-to-say, although I turned these and several other ideas over in my head, I decided that printing up all the new truck and supply units (as well as the now necessary "de-motorized" markers for both sides) was just more than I wanted to deal with at the time. Oddly, however, this idea still appeals to me even to this day!

Best Regards, Joe

Greetings Again Tom:

I saw your comment this morning and, although I was busy at the time with another project, I rushed off a reply. I retrospect, I can see that I neglected to really craft a full response to your several interesting proposals; so, I'm going to try again, now that I have a little more time.

First, my idea -- which was implied, but not clearly stated -- was that attacks should actually require access to physical supply units (as they do, for instance, in SEELOWE or PAA); further, that attacks could be supplied at one of three different levels: minimum (half attack strength); normal (printed attack strength); and maximum (double attack strength, but supply unit is removed at the end of the combat phase).

Second, because roads in the Soviet Union were both in short supply and generally primitive, railroads were -- as you yourself note -- the key to supplying both the German Army's advanced spearheads during the early years of the war, and the Red Army's "steamroller" in the later years of the fighting, once the tide had finally turned against the Wehrmacht. This suggests (as I discussed in an earlier post) that some sort of realistic limits (but not draconian restraints) must be placed on the RR repair capabilities of both armies.

Third, your suggestion that supply units should have a very limited movement capability is a good one. Horse-drawn transport isn't fast, but it was certainly essential to both armies in Russia during World War II; in fact, in some cases it was literally the only thing that could move, however slowly. And although it has been awhile since I looked at any of the "nitty-gritty" logistical data for the War in the East, I seem to recall that the typical "Panje Wagon" could cover about 10 to 15 kilometers a day on reasonably good roads during dry weather, but that they were often reduced to a fraction of that during mud and snow weather.

Fourth, the idea about "depots" is a good one; in fact, pretty much the same idea occured to me after I looked at Frank Davis' MODULE ONE treatment of World War I. At the time, I thought that the best "historical" option would probably be to maintain the "fog of war" by concealing, through the use of "dummy" counters, both the movement and the location of supply units prior to their actual use. In short, both players would be able to accumulate supplies behind their respective frontlines without the opposing commander really knowing for sure where the real attacks were intended until the battles actually began.

In any case, thanks again for your thoughtful comments and Best Regards, Joe

Joe, here are few more halfbaked thoughts on supply rules;

From S&T 25

20 Trucks =120 Tons and 200 Miles in day

40 Wagons w/100 Horses = 30 Tons and 20 miles in day.

Also from S&T the German (and other western) armies were 80+% non-combat troops versus 20% for the Soviets. This should be reflexed in the supply capabilities.

If you had different counters for the truck and wagon the Truck units should have a mp of 10 versus 1 for the wagon units.

(Full) Attack supply can only be draw from depot units.

Depot units can only be placed on rail lines or next to rivers that connect to a home city/rail.

Moving a depot is multi turn process during which the depot can not provide supply, but shorter for the Germans.

Mech units can draw attack supply a fairly long distance and move in the same turn.

Inf units draw attack supply from HQs. HQs have a transport capacity (higher for Germans, or Guards?). The capacity is used to fetch supply from depots and to move it sub units. E.G. a HQ with a cap of 20 and five hexes from a depot could fetch 4 Supply counters and place them on the HQ chit or deliver 10 supply chits already on the HQ to 10 units at an average distance of 2 hexes.

(Russian) Infantry can not move and receive attack supply unless moving towards the HQ/Depot

Germans HQs can use transport capacity to move supply chits directly from the depot to units or to stockpile supply in empty hexes.

Tom

Not all "non-combat" troops are supply sergeants, or even necessarily in involved in logistics. That includes, signal, finance, etc. The US, especially, is REMF-heavy. I'd be willing to bet that the percentage of "non-combat" troops (the percent of the percent) dedicated to direct support of the fighters was higher in the Soviet than ours. Why? Because they also needed to keep their guys fighting, they just were not quite as concerned with making them comfortable while doing so. ;-)

Greetings Tom:

I was away from the computer all day yesterday, so I am only now in a position to respond to your latest points; better late than never, I suppose.

Regarding S&T and its projected lift capabilities for both trucks and horse-drawn drayage during World War II, I hate to say it, but Dunnigan's figures can largely be ignored when it comes to the Eastern Front. In the case of trucks, for example, the motorized transport assets of the Wehrmacht were eroding at the rate of about 5% per month (with light use) prior to the campaign against France in 1940; in fact, it was only the addition of the vehicles that the Germans were able to loot from other countries prior to the invasion, that induced the OKH to table plans that it had already made to DEMOTORIZE two divisions so as to relax the strain on the German economy from the military's ongoing demand for new trucks. The situation when it came to horse-drawn wagons, however, was infinitly worse; and having worked with horses,as a professional, for many, many years, this is something about which I know a great deal.

First, the transport capabilities described in S&T, if I were to guess, seem pertain to the road and forage conditions found in much of Western and Central Europe. Russia, on the other hand, was a very different situation entirely. To understand why this is so, it is necessary to understand what is required to maintain the health of a "real" rather than a "paper" horse. Food, of course, is the first issue: a typical military mount (or artillery horse) in LIGHT work needs to be fed about 2.5% (think 25lbs. of grain and roughage) of its body weight each and every day; when engaged in strenuous work, this increases to 30-35 lbs. of feed (again, every day). Interestingly, because of the delicate nature of the horse's digestive tract, only about 20-30% of this feed can be grain -- the rest MUST be roughage; if it is not, the horse will usually colic or "tie-up" fairly quickly and become unuseable. This is why the Germans rapidly resorted to the smaller, hardier Russian ponies (the Panjes, instead of the larger European warmbloods): they couldn't pull as much weight as the double-pairs, because they were smaller and typically harnessed individually or in single pairs; but they could "soldier on" when the larger horses failed. This meant that drayage was slower and less-efficient, but it also meant that the supplies being transported to the front actually had a reasonable prospect of arriving.

The second issue, as alluded to earlier, is that of the roads and tracks in Russia. They were, for the most part, narrower and in much worse condition than those of Western Europe. This is no small thing because it meant, in certain areas and during certain times of year, many tracks were capable of only supporting one-way traffic. The problems that one-way traffic imposes on moving troops (a panzer division is 20 kilometers long, for instance, when in road march), or supplying them once they had moved, is obvious enough that it does not equire any further exposition.

Finally, I apologize for launching into a minor rant about horses, but the sorry treatment of military horses thoughout history has, for a long time, been one of my pet peeves. The wastage among Napoleon's horses in Russia during his 1812 campaign is well-known; but the fact that the Allied armies, during World War I, virtually decimated the horse populations of England, France, and Belgium after only six months of war is not so well known. It does, however, explain why the Allies imported over 1,000,000 horses from America and Canada to make good their horrific (and often needless) losses.

Best Regards, Joe

Greetings (finally) Preston:

Yes, much is made of the "leaner" more combat effective profile of Soviet versus western armies; however, this is not quite as "cut and dried" as the numbers might indicate. For one thing, Soviet rifle divisions, during World War II, tended to be much smaller (typically about one third the actual manpower) of a full-strength American infantry division. Secondly, because the Red Army was -- until the last year of the war -- fighting on its native soil, it could (and did) call on civilians (volunteers or otherwise) to support many of its rear area needs; something that the American army did not do.

Interestingly, modern US military doctrine has called for a significant increase in the numbers of civilian support personnel as a means of freeing up more uniformed troops for combat operations. Thus, in at least one sense, the US military has returned, in the last few decades, to a system of civilian rear area support that had largely been abandonned after the Civil War.

Finally, your point about all those mail clerks, cooks, mechanics, and other non-combat personnel that tended to be clustered in the immediate rear of the American frontline is also a valid one: the Germans learned, much to their surprise during the Battle of the Bulge, that American commanders could, when necessary, scrape up an astounding number of second line troops to replace their short-term combat losses in an emergency.

Best Regards, Joe

Greetings Again Tom:

After considering our discussion, thus far, I have a few additional thoughts on rationalizing the logistical/combat systems of WItE and DNO/UNT.

First, because the wastage of German trucks in Russia was two to three times what it was in France, it is pretty clear that while transport losses might be made up in 1941-42, as the demands from other Axis fronts (France and Italy) increased, starting in 1943, the condition of German motorized transport steadily worsened as the war continued i nto its last few years. This problem was greatly magnified by the vast number of American Dodge trucks (20,000 +) that were shipped to Russia beginning in late 1942.

For the Germans, the one saving grace "logistically speaking" was that, as they were driven back by the Red Army, the could largely rely on rail and water-borne transport to pick up the slack. Thanks to the failure of the Red Air Force to really develop any kind of effective air interdiction strategy(e.g., the bombing of German marshalling yards, bridges, tunnels and double rail lines), the Russians were left to depend on the largely ineffective operations of the anti-Axis partisan bands in the German rear areas.

Best Regards, Joe

Joe, I just realised I never thanked Barbara for her advice on the email notification thing. Belatedly, thank you.

Greetings Ian R:

Don't mention it; she is always happy to help my readers when she can.

Best Regards, Joe