TAHGC, MAHARAJA (1994)0 comments

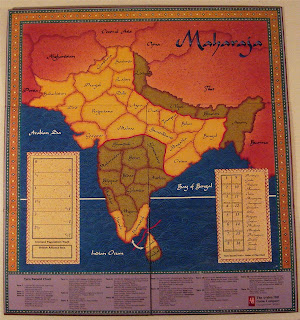

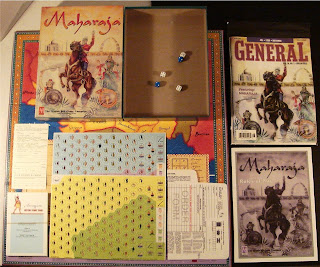

MAHARAJA is a multi-player simulation of the turbulent history of the Indian subcontinent that spans over thirty-three hundred years of migrations, invasions, wars, and the rise and fall of nations, cultures, and empires. MAHARAJA is a historical tour that immerses its players in the peoples and events that ultimately coalesced to lay the cultural foundation for the modern world’s most populous democracy. MAHARAJA was designed by Craig Sandercock and published in 1994 by the Avalon Hill Game Company (TAHGC).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDBritain’s conquest of India began, as it had with so much of the rest of the British Empire, with the arrival of the first English traders. In 1617, the English East India Company's toehold on the subcontinent expanded when it was formally granted trading rights by the Mogul Empire; once these commercial privileges had been secured, the East India Company wasted no time but quickly set about building shipping centers and depots at strategic locations along the Indian Coast. Of course, once these various enclaves had been established, it was only sensible for the British to build forts to protect their gradually expanding commercial holdings. The next stage, for these early representatives of the British Crown, like the first, was inevitable: once company forts had been established, it followed, as the night follows the day, that it was then essential for the East India Company to raise a private army to garrison these newly-erected forts and to protect its ever-expanding territorial and commercial interests. Moreover, in the eyes of these ambitious English traders, a private army was, not surprisingly, considered to be a very handy thing to have.During the next century, the East India Company steadily increased its land holdings and its local political influence by shrewdly supporting one local tribal leader against another in the numerous internecine wars that plagued India during the fractious period of the Mogul decline. The British, however, were not alone among the European powers in their determination to ultimately take control of the Indian subcontinent; their main competitors — the unpleasant and always quarrelsome French— had also established a foothold in India through the economic and military machinations of the East India Company’s Gallic doppelganger, the Compagnie française des Indes orientales. As time passed, friction between the two European companies only grew, and a major clash between the French and British gradually came to be seen by both as being inevitable. Finally, the increasingly bitter trading rivals resorted to what must have seemed perfectly natural to two commercial adversaries both of which employed their own private armies: they went to war with each other. In the 1740s and 1750s, a series of military engagements, known collectively as the 'Carnatic Wars' was fought between the soldiers, agents, and allies of the two competing trading companies. In 1757, a British force led by Robert Clive (that’s right: the 'Clive of India') decisively defeated the French and their Indian allies at the Battle of Plassey. This crushing victory over Britain’s only remaining adversary left the English East India Company in undisputed control of Bengal and established it, at long last, as the preeminent political and military power in India. It also meant that Indian self-rule was now doomed. Clive’s military success had far-reaching effects for both England and for India. The British victory at Plassey not only disposed of the French, it also cleared away the last serious obstacle to English domination of the Indian subcontinent; the establishment of the British Raj was now only a matter of time. DESCRIPTION MAHARAJA is a grand strategic simulation on a truly epic scale. It is a game — like its predecessor and close relative, BRITANNIA — for those players who genuinely take the long view of history. The game covers the dynamic, exciting, and often violent period in India’s history from the early Aryan invasions, beginning around 1500 B.C., to the colonial conquest of the subcontinent by the British in 1850 A.D. MAHARAJA is intended to be a multi-player game: each player is assigned a color prior to the start of play; each player color determines which nations (peoples) a player will control over the course of the entire game. These different nations each appear during specific historical periods (game turns) and compete with the nations of other players for control of geographical regions on the game map. In the course of the game, players will attempt to amass victory points using armies, population markers, and leaders. Victory points can only be gained through the occupation of areas, conquest of opposing nations’ areas, destruction of enemy units, and the acquisition of raj points. The game’s winner is the player with the most points at the end of the last (16th) game turn. MAHARAJA is a grand strategic simulation on a truly epic scale. It is a game — like its predecessor and close relative, BRITANNIA — for those players who genuinely take the long view of history. The game covers the dynamic, exciting, and often violent period in India’s history from the early Aryan invasions, beginning around 1500 B.C., to the colonial conquest of the subcontinent by the British in 1850 A.D. MAHARAJA is intended to be a multi-player game: each player is assigned a color prior to the start of play; each player color determines which nations (peoples) a player will control over the course of the entire game. These different nations each appear during specific historical periods (game turns) and compete with the nations of other players for control of geographical regions on the game map. In the course of the game, players will attempt to amass victory points using armies, population markers, and leaders. Victory points can only be gained through the occupation of areas, conquest of opposing nations’ areas, destruction of enemy units, and the acquisition of raj points. The game’s winner is the player with the most points at the end of the last (16th) game turn.  MAHARAJA uses a game system that is comparatively simple, yet unpredictable. For starters, the game is played with a variable player turn order: players move their units according to the order outlined on the Nation Control List. A typical game turn proceeds with the following strictly-ordered sequence of player actions: Increase Population Phase; Invasion Phase; Movement Phase; Battle Phase; Factory Phase; Arms Phase; and, at the end of certain game turns, the Victory Point Count Phase. In the course of the game, players will find themselves variously in control of weak and strong nations. Thus, players will accumulate victory points at different rates during different historical epochs. Not to worry though, the ingenious game design balances out these inequalities over the span of the whole game, so that the victory point opportunities of the different players wax and wane as the game progresses and new nations enter play. Another interesting feature of MAHARAJA is that at different stages in the game, players may find themselves controlling several different nations that are in direct competition for the same geographical areas. Thus, in order to gain and keep victory points, a player may occasionally be obliged to attack himself! MAHARAJA offers not only a standard four-player version of the game, but also a five-player, and a standard and shortened three-player version, as well. There are no optional rules. MAHARAJA uses a game system that is comparatively simple, yet unpredictable. For starters, the game is played with a variable player turn order: players move their units according to the order outlined on the Nation Control List. A typical game turn proceeds with the following strictly-ordered sequence of player actions: Increase Population Phase; Invasion Phase; Movement Phase; Battle Phase; Factory Phase; Arms Phase; and, at the end of certain game turns, the Victory Point Count Phase. In the course of the game, players will find themselves variously in control of weak and strong nations. Thus, players will accumulate victory points at different rates during different historical epochs. Not to worry though, the ingenious game design balances out these inequalities over the span of the whole game, so that the victory point opportunities of the different players wax and wane as the game progresses and new nations enter play. Another interesting feature of MAHARAJA is that at different stages in the game, players may find themselves controlling several different nations that are in direct competition for the same geographical areas. Thus, in order to gain and keep victory points, a player may occasionally be obliged to attack himself! MAHARAJA offers not only a standard four-player version of the game, but also a five-player, and a standard and shortened three-player version, as well. There are no optional rules. A PERSONAL OBSERVATION Some players, it goes without saying, like multi-player games that attempt to capture the broad sweep of history, and some don’t. For my own part, the personalities of the other players at the table are at least as important as the game being played. A convivial group of gamers can make even a relative "dog" a pleasure to play. MAHARAJA is far from a dog, and even accepting that some of the game’s history is a little dodgy — the whole Aryan Invasion Theory has recently come under fire, for instance — it nonetheless is an informative and enjoyable game when sitting in with the right company. For that reason, although MAHARAJA is certainly not my favorite multi-player game of this type, I still feel comfortable recommending it. Based on my own experience at the game table, I would say that anyone who likes BRITTANIA will almost certainly like this game. In terms of play, MAHARAJA requires a nice mix of diplomacy, luck, guile, and tactical acumen in order to win. In addition, it also has the unexpected advantage of painlessly teaching the players about an epoch in the Indian subcontinent’s history about which most of us in the West know far too little! Some players, it goes without saying, like multi-player games that attempt to capture the broad sweep of history, and some don’t. For my own part, the personalities of the other players at the table are at least as important as the game being played. A convivial group of gamers can make even a relative "dog" a pleasure to play. MAHARAJA is far from a dog, and even accepting that some of the game’s history is a little dodgy — the whole Aryan Invasion Theory has recently come under fire, for instance — it nonetheless is an informative and enjoyable game when sitting in with the right company. For that reason, although MAHARAJA is certainly not my favorite multi-player game of this type, I still feel comfortable recommending it. Based on my own experience at the game table, I would say that anyone who likes BRITTANIA will almost certainly like this game. In terms of play, MAHARAJA requires a nice mix of diplomacy, luck, guile, and tactical acumen in order to win. In addition, it also has the unexpected advantage of painlessly teaching the players about an epoch in the Indian subcontinent’s history about which most of us in the West know far too little! Design Characteristics:

Game Components:

GDW, 1942 (1978)2 comments

1942 is an operational-level (battalion/regimental/division) simulation of ground combat during the first five months of the Japanese offensive in the Pacific Theater in World War II. The game was designed by Marc Miller and published in 1978 by Game Designer’ Workshop (GDW). 1942 is one of GDW’s “Series 120” games. These titles were intended to be “introductory” games; the “120 Series” label comes from the fact that each of these games uses no more than 120 counters, and all were designed to be played to completion in two hours or less.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDOver seven thousand islands collectively make up the Philippine Archipelago. This vast concentration of large and small islands lies only 500 miles from the coast of China, and, because of this position, the Philippine Islands dominate the eastern shipping lanes through the South China Sea. The United States first seized the Philippine Islands from Spain in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, and the advantages to the United States of American control of this former Spanish colony were obvious from the outset. The serendipitous location of the Philippines quickly made the archipelago an important commercial center for American companies with economic interests in Asia; it also made it an excellent base for American naval forces in the Far East. This fact was not lost on other national players in the region and, as time passed, unfriendly eyes began to covet this American Asiatic possession; eyes that belonged to the senior officers of the general staff of the expansionist and increasingly bellicose Empire of Japan.The United States and Japan had not always been adversaries. In fact, the two rising Pacific powers had been Allies during the First World War; unfortunately, in the decades that followed the “War to end all Wars,” the two countries had repeatedly clashed diplomatically over Japan’s escalating war of conquest against China. And as the relations between Japan and the United States continued to deteriorate in the mid-1930s, the Japanese High Command began secret military preparations to wrest the Philippine Islands from America’s control. The islands’ strategic location made the subjugation of the Philippines — and particularly the archipelago’s most important island, Luzon — essential to future Japanese plans for military expansion into the rest of Southeast Asia. And such an expansion was essential to Japan's ambitious future Imperial designs in the Pacific. Japan had no significant natural resources of its own; however, the coal, oil, rubber, tin, iron ore, nickel, and agricultural lands that Japan needed to support its expanding industries and to feed its growing population were all within easy striking distance of the Empire’s powerful army and navy. Unfortunately, to seize these prizes, Japan would have to take them by force from the British, Dutch, and Americans. America and her European allies, not surprisingly, were not oblivious either to Japan’s Imperial ambitions or to the military threat those ambitions posed to American and European holdings in the region. Moreover, the critical importance of these islands was as obvious to American military leaders as it was to the Japanese. Thus, when General Douglas MacArthur was recalled to active duty on 26 July 1941 to serve as the supreme commander of all forces in the Philippines, he immediately set about planning for a robust and aggressive defense of Luzon. Philippine defenses were, the new commander discovered soon after taking charge, woefully inadequate. Nonetheless, the always confident General MacArthur was certain that, once promised reinforcements and modern equipment from the U.S. had arrived in the Philippines, Luzon could be successfully held against even a large-scale and determined enemy invasion. His target date for completion of his defensive preparations was April, 1942. Unfortunately for MacArthur, his army, and the Filipino people, the Imperial Japanese Army had a timetable of its own. On 8 December 1941, Japanese bombers from Formosa struck American airfields on Luzon. Almost half of all of the U.S. Army’s modern fighters as well as recently-arrived B-17 bombers were destroyed on the ground. On 10 December, the Japanese began amphibious landings against the northern end of Luzon. Small Japanese detachments landed at Gonzaga, Appari, Ladag, and Vigan and seized airfields so that incoming Japanese planes could be based directly on the island. And this was only the beginning. On 12 December a small Japanese force of 2,500 landed on the southern tip of the island at Legaspi and rapidly marched north. On 22 and 24 December 1941, the main body of General Homma’s Fourteenth Army finally came ashore on Luzon without meeting any serious interference. The invasion phase of the Japanese plan, by any standard, had been a complete success, the next phase — the battle for control of Luzon and with it, the rest of the Philippines — was now ready to go forward. DESCRIPTION 1942 is a two-player simulation of the first five months of the Japanese ground offensive in the Pacific. Beginning in December 1941, Japan launched attacks against Western forces in Pearl Harbor, Malaya, the Philippine Islands, Java, and Hong Kong. The game focuses on the initial period — December 1941 to May 1942 — of Japanese expansion into Southeast Asia, and of the Allies’ attempt to stem Imperial Japan’s tide of conquest. 1942 is a two-player simulation of the first five months of the Japanese ground offensive in the Pacific. Beginning in December 1941, Japan launched attacks against Western forces in Pearl Harbor, Malaya, the Philippine Islands, Java, and Hong Kong. The game focuses on the initial period — December 1941 to May 1942 — of Japanese expansion into Southeast Asia, and of the Allies’ attempt to stem Imperial Japan’s tide of conquest. Because 1942 is intended by the designer to be an “introductory” game, the game system is orthodox, comparatively simple, and intuitively logical. The counters represent the military units — American and Filipinos, British, Dutch, and Japanese — that actually fought in the historical campaign. The area represented by the game map covers that region of Southeast Asia over which the Allies and Japanese battled for control. 1942 is played in game turns, each of which represents a fortnight (roughly two weeks) of real time. Each game turn is further divided into an Allied and a Japanese player turn; the Allied player is always the first player to act in any turn.  However, the game begins with a special Japanese Attack game turn (turn “0”) during which only the Japanese player may move and attack; the game then continues with its standard format for ten more regular game turns. Each game turn in 1942 follows an ordered series of player actions and proceeds as follows: Allied Movement Phase; Allied Combat Phase; Japanese Movement Phase; and Japanese Combat Phase. The Movement Phase of each player turn is further subdivided into three strictly ordered player actions: the Land Movement Segment; the Air Movement Segment; and finally, the Naval Movement Segment. In keeping with the “introductory” intent of the designer, the rest of the rules are also comparatively clear and easy to understand, even for a comparative novice. All ground units possess a zone of control (ZOC). In addition, these ZOCs are rigid, but not “sticky,” and combat is voluntary between adjacent enemy units. Supply rules, although important to the play of the game, are refreshingly uncomplicated. Stacking rules are also simple: four ground units of the same side may stack in a single hex; stacking rules are different for fortresses, however, and air units may not stack with other air units. However, the game begins with a special Japanese Attack game turn (turn “0”) during which only the Japanese player may move and attack; the game then continues with its standard format for ten more regular game turns. Each game turn in 1942 follows an ordered series of player actions and proceeds as follows: Allied Movement Phase; Allied Combat Phase; Japanese Movement Phase; and Japanese Combat Phase. The Movement Phase of each player turn is further subdivided into three strictly ordered player actions: the Land Movement Segment; the Air Movement Segment; and finally, the Naval Movement Segment. In keeping with the “introductory” intent of the designer, the rest of the rules are also comparatively clear and easy to understand, even for a comparative novice. All ground units possess a zone of control (ZOC). In addition, these ZOCs are rigid, but not “sticky,” and combat is voluntary between adjacent enemy units. Supply rules, although important to the play of the game, are refreshingly uncomplicated. Stacking rules are also simple: four ground units of the same side may stack in a single hex; stacking rules are different for fortresses, however, and air units may not stack with other air units.Combat is resolved using a traditional “odds differential” Combat Results Table. Terrain, itself, has no effect on combat; those factors that do influence combat are expressed through die-roll modifications (DRMs). Air and amphibious operations are an integral part of the game and are handled abstractly but with logical simplicity. The game’s winner is determined by comparing each side’s victory point totals at the conclusion of game turn ten. Victory points — as might be expected, given the Japanese military's strategic goals — are gained through the capture of certain geographical objectives and also through the destruction (surrender) of enemy units. In addition, the Allies receive victory points for any Allied units still surviving on the game map at game end. 1942 offers two scenarios: the Historical Dispositions Scenario; and the Allied Optional Dispositions Scenario. There are no other “optional” rules. A PERSONAL OBSERVATION First, a brief note on what 1942 is not. It is not VICTORY IN THE PACIFIC or USN without ship counters. The narrow, operational scope of the game, both in terms of geography and in terms of time scale, is much shorter and less complicated than either of these other two titles. What it is, instead, is a relatively simple simulation of the initial, widely-dispersed Japanese military operations that actually set off the War in the Pacific. The Japanese plan of conquest was both extraordinarily ambitious and audacious. Moreover, the independent ground campaigns to drive the Allies out of Malaya, Hong Kong, Java, and the Philippines during the first days of the war all presented their own sets of unique challenges. Extremely tight operational timetables, and real limitations in available airpower, sea lift, naval warships, and in ground forces all could have produced a Japanese defeat — if not a military disaster — had any major element of the Japanese strategic plan gone wrong. Time and manpower were the major stumbling blocks for the Emperor’s military commanders; the Japanese were chronically short of both during the early months of the war. Yet the Imperial ground, air and naval forces won one decisive victory after another, often against formidable odds. It is how the Japanese achieved these stunning results and what the Allies might have done to thwart them that Marc Miller attempts to simulate in 1942. First, a brief note on what 1942 is not. It is not VICTORY IN THE PACIFIC or USN without ship counters. The narrow, operational scope of the game, both in terms of geography and in terms of time scale, is much shorter and less complicated than either of these other two titles. What it is, instead, is a relatively simple simulation of the initial, widely-dispersed Japanese military operations that actually set off the War in the Pacific. The Japanese plan of conquest was both extraordinarily ambitious and audacious. Moreover, the independent ground campaigns to drive the Allies out of Malaya, Hong Kong, Java, and the Philippines during the first days of the war all presented their own sets of unique challenges. Extremely tight operational timetables, and real limitations in available airpower, sea lift, naval warships, and in ground forces all could have produced a Japanese defeat — if not a military disaster — had any major element of the Japanese strategic plan gone wrong. Time and manpower were the major stumbling blocks for the Emperor’s military commanders; the Japanese were chronically short of both during the early months of the war. Yet the Imperial ground, air and naval forces won one decisive victory after another, often against formidable odds. It is how the Japanese achieved these stunning results and what the Allies might have done to thwart them that Marc Miller attempts to simulate in 1942. In a more general vein, I cannot resist making an observation or two about GDW’s quirky attempt at producing simple, easy-to-play, inexpensive games. GDW’s foray into the design and publication of simple, introductory games was, to be generous, pretty much a bust. AGINCOURT was too simple, visually nondescript (green and brown, that’s the best you could do for counters in the age of heraldry?) and boringly repetitive in its play; BEDA FOMM and ALMA were interesting games, but probably a bit too complicated for the typical beginner. And these disappointing examples were not alone: more than a few of the other “120” titles shared the unfortunate attributes of being both time-consuming to learn and boring to play, once they were learned. That being said, I personally think that of all of the “120 Series” of games, 1940, 1941, and 1942 all probably come closest to fulfilling the original design goals set by the “boys from Normal” for the “120 Series.” Over the years, I have played every one of these World War II titles and, to varying degrees, liked them all. My personal favorite of the three, I have to confess, remains 1940. I don’t know why, but the very different strategic problems confronting both the Allies and the Germans in the spring of 1940, have always intrigued me. Nonetheless, I also spent many enjoyable hours playing the other two titles, and I and a few of my friends continued, off and on, to play them for years after they first appeared. And these World War II titles all have something else going for them, as well: despite the different campaigns that each of these three GDW games represents in game form, I think that they all share several qualities that are critical to the long-term success of any “introductory" game. That is: they are all three comparatively easy-to-learn, interesting, and fast-paced to play. In addition, because of the unique military problems presented in every one of these titles, I believe that each of them can be challenging and fun for the experienced player, while still being enjoyable for the hobby novice. Design Characteristics:

Game Components:

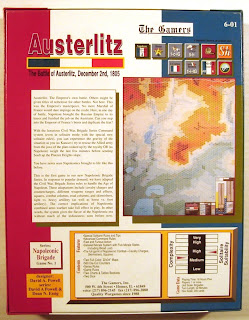

THE GAMERS, AUSTERLITZ (1993)0 comments

AUSTERLITZ is a historical simulation, at the brigade tactical level, of the climactic battle on 2 December 1805 that determined the final outcome of Napoleon’s 1805 campaign against the armies of Russia and Austria. The game was designed by David A. Powell, and published in 1993 by The Gamers, Inc (TGI). AUSTERLITZ is the first installment in TGI’s Napoleonic Brigade Series of games.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Tsar Alexander I, 1812 . At 8:00 am on 2 December 1805, near the small Moravian hamlet of Austerlitz, the 85,000 soldiers of the Third Coalition army threw themselves forward in a determined attack against the 67,000 Frenchmen of Napoleon’s Grand Armée. This combined army of Russian and Austrian troops, commanded by Tsar Alexander I, massed almost half of its strength in four large columns and advanced through the morning fog to crash into Napoleon’s weak right flank near the villages of Telnitz and Sokolnitz. The winter battle seemed to begin well for the attackers as the French troops retreated in the face of the powerful Allied assault. Those officers and nobles commanding the Russo-Austrian Army were confident that they would break the French flank and sever Napoleon’s communications with Vienna. But even as the Allied advance appeared to be gaining momentum, the 7,000 French troops of Marshal Davout’s IIIrd Corps, after having force marched a distance of some seventy miles to reach the battlefield, arrived on Napoleon’s right just in time to reinforce its wavering line. The Russo-Austrian commanders, fixated on continuing their attack, stripped more and more troops away from the coalition center on the Pratzen Heights in order to reinforce their left. At 9:00am Napoleon unleashed part of his reserve from the fog-shrouded valley just below the heights to smash into the Allied center and seize the high ground. As the French began their assault, the “Sun of Austerlitz” finally broke through the haze and lit the heights. The conflict would continue with bitter fighting well into the evening, but Napoleon had, for all intents and purposes, won the battle with one masterful stroke, once his troops captured the Pratzen heights and broke the Russo-Austrian center. DESCRIPTION TGI’s AUSTRLITZ is a grand tactical (brigade/regiment) level simulation — based loosely on the CIVIL WAR BRIGADE Game System — of the final crucial battle in Napoleon’s 1805 campaign against Austria and Russia. The French Emperor’s decisive victory at Austerlitz clearly signaled that Napoleon had now become the dominant political and military strongman in Europe. And so he would remain for another decade, despite the constant machinations of the British Empire and the persistent military efforts of the reactionary monarchies of Europe. TGI’s AUSTRLITZ is a grand tactical (brigade/regiment) level simulation — based loosely on the CIVIL WAR BRIGADE Game System — of the final crucial battle in Napoleon’s 1805 campaign against Austria and Russia. The French Emperor’s decisive victory at Austerlitz clearly signaled that Napoleon had now become the dominant political and military strongman in Europe. And so he would remain for another decade, despite the constant machinations of the British Empire and the persistent military efforts of the reactionary monarchies of Europe. AUSTERLITZ is played in game turns, and each game turn is further divided into five interwoven player phases. These strictly-sequenced game phases proceed as follows: the Command Phase; the Cavalry Charge Phase; the Movement and Close Combat Phase; the Fire Combat Phase; and finally, the Rally Phase. Once both sides have completed their respective player turns, the game turn marker is advanced one space, and the turn sequence is again repeated until the scenario ends. The historical detail presented by the Napoleonic Brigade Series Game System is especially evident in the specific player actions required during each turn phase. For example, just the first operation of a player turn, the Command Phase, is made up of five distinct segments, or sub-routines: Order Issue (during this segment, the phasing player generates and records new orders up the limit imposed by his command points); Corps Attack Stoppage Checks (if any of the phasing player’s attacking corps received enemy fire from two hexes distance or less during the preceding turn, these corps must now individually check to see if their attack continues, is stopped, or is repulsed); Initiative Order Determination (at this time, the phasing player rolls a die to attempt to establish initiative for individual leaders); Delay Reduction (during this phase, any leaders who have had their orders encumbered by any sort of “delay status” check to see if their delay status ends); and New Order Acceptance (the phasing player now rolls to see if the orders delivered this turn are accepted, delayed, or misunderstood).  The game mechanics of TGI’s AUSTERLITZ, although fairly complex, are intuitively logical and, once learned, are not difficult to execute. None-the-less, the game’s functions — despite their similarity to other Napoleonic battle games — do require some study on the part of new players before they can be mastered. The overall design architecture of the game is, given its subject matter and scale, more-or-less familiar. Stacking rules are detailed but reasonable; both the various types of terrain and elevation influence combat, typically through column shifts on the combat results tables (CRTs). Units do not possess zones of control (ZOCs). Combat, as might be expected, can be divided into three general categories: Fire Combat (both small arms and artillery); Cavalry Charge (shock); and Close Assault (infantry shock). Combat losses are administered through a combination of Morale Checks, Straggler Checks, and Step-Losses, and individual commanders can be wounded or killed as a result of combat. Leadership, command and control, and morale — as was the case historically — are all critical to the outcome of the battle. In addition, the game incorporates a number of elements that contribute both the texture of the game and to its “period” feel. Thus, rules covering unit facing, skirmisher units, line of sight, different infantry formations (square, line, column, and road march), forced marches, ammunition supply (both small arms and artillery), night operations, and the “fog of war” all play their part in the flow of play in AUSTERLITZ. The one somewhat cumbersome aspect of the Napoleonic Brigade Series Game System derives from the record-keeping necessary to track ongoing unit step-losses and the status of orders. However, even this aspect of the game is considerably simplified by the inclusion of detailed, easy-to-use “master” record sheets that can be photocopied as the need arises.  Victory in the game is determined by a comparison of battlefield losses. Because the purpose of battle, at least in the eyes of Napoleon, was to crush the enemy army and by so doing end the enemy commander’s will to resist, the winner in AUSTERLITZ is based on the destruction of enemy units, the wrecking of larger formations (corps and columns), and the killing or wounding of enemy leaders. The game’s winner is the player that satisfies the victory requirements of the specific scenario being played. Victory in the game is determined by a comparison of battlefield losses. Because the purpose of battle, at least in the eyes of Napoleon, was to crush the enemy army and by so doing end the enemy commander’s will to resist, the winner in AUSTERLITZ is based on the destruction of enemy units, the wrecking of larger formations (corps and columns), and the killing or wounding of enemy leaders. The game’s winner is the player that satisfies the victory requirements of the specific scenario being played.  TGI’s AUSTERLITZ offers five scenarios: Scenario 1: Battle for the Goldbach Stream (9 game turns); Scenario 2: The Olmutz Road (8 turns long); Scenario 3: The Sun of Austerlitz (23 game turns); Scenario 4: Katusov in Command! (23 turns); and Scenario 5: The Advance to Battle (50 game turns). The first two scenarios are short enough to serve as introductions to the larger game; scenarios 3 and 4 offer two approaches to simulating the historical events of the Battle of Austerlitz; the last scenario covers two full days of action beginning with the advance to contact with Napoleon’s army by the combined Austro-Russian army on 1 December, and culminating with a simulation of the actions of the two opposing armies throughout the actual day of battle, 2 December 1805. TGI’s AUSTERLITZ offers five scenarios: Scenario 1: Battle for the Goldbach Stream (9 game turns); Scenario 2: The Olmutz Road (8 turns long); Scenario 3: The Sun of Austerlitz (23 game turns); Scenario 4: Katusov in Command! (23 turns); and Scenario 5: The Advance to Battle (50 game turns). The first two scenarios are short enough to serve as introductions to the larger game; scenarios 3 and 4 offer two approaches to simulating the historical events of the Battle of Austerlitz; the last scenario covers two full days of action beginning with the advance to contact with Napoleon’s army by the combined Austro-Russian army on 1 December, and culminating with a simulation of the actions of the two opposing armies throughout the actual day of battle, 2 December 1805. A PERSONAL OBSERVATIONCoalition cavalry in action at Austerlitz. Napoleon fought over seventy battles in his long military career, but the Battle of Austerlitz was his masterpiece. Through a combination of feigned weakness, acting, nerve, and superb timing, the French Emperor first drew an enemy army that did not need to fight into accepting a major battle on ground of Napoleon’s choosing, and then, by purposefully and visibly weakening his right, insured that his enemies would confidently march into a tactical trap from which there would be no escape. The battle raged from dawn to dusk, but Napoleon’s decisive victory was assured within the first few hours of the opening cannonade. Time would march on, and the French Emperor would live to win many more battles before his dominance of European affairs was finally ended in 1815; in all the bloody, strife-filled years that followed this single winter’s day victory, however, he would never enjoy another battlefield success to match 2 December 1805, and the brilliance of the blazing “Sun of Austerlitz.” French Cuirassiers about to charge at Austerlitz. AUSTERLITZ is the first installment in The Gamers’ Napoleonic Brigade Series of tactical simulations of battles from the Age of Napoleon. It is, to a large degree, a natural outgrowth of TGI’s Civil War Brigade Series, and as such, there is much in this game system that will be familiar to those gamers who have played any of the CWB Series games. There is also, however, a great deal that is different. The rifled muzzle-loading muskets of the American Civil War had both greater accuracy and greater range than the smoothbore muskets of the Napoleonic Wars. Cavalry and galloper guns could, with relative safety, approach much closer to an enemy firing line during the early years of the nineteenth century than they could by the 1860s. For this reason, the battlefield dominance of artillery and the shock power of cavalry are both much more significant in AUSTERLITZ than in the CWB titles. This greater variety of potential battlefield threats also explains the expanded number of different infantry formations found in AUSTERLITZ. Thus, from the simple infantry line and square, to the column and even the combination of infantry line and column represented by the ordre mixte, these various formations all had an important place on the Napoleonic battlefield. General Rapp reports to Napoleon at Austerlitz. TGI’s AUSTERLITZ is not a simple game. None-the-less, the rules are clearly enough written that a player totally unfamiliar with the NBS system can, with a little work, probably understand the basic substance of the game without a lot of help; players familiar with the CWB Series rules, as might be expected, should have little difficulty learning the game in the course of one or two play-throughs. That being said, this title is probably not a good choice for novices. The game system is just too detailed and richly textured. Still, the heart of the combat system: the tactical subroutines — although a little cumbersome for new players when they are initially learning the game — are intuitively logical and historically reasonable. And the flow and tempo of the game combine to produce a realistic, yet manageable simulation of Napoleonic warfare. Finally, AUSTERLITZ has, at least to my eye, excellent graphics and nice visual appeal. The two glossy paper map sheets are attractive and unambiguous. The rules and player aids, although detailed and fairly lengthy, are clear and easy to use. Best of all, the back-printed unit counters are — as has become more and more common among the most recent batch of Napoleonic titles — both utilitarian and quite appealing to the eye. In short, TGI’s AUSTERLITZ is historically colorful, exciting, and — once the game system is mastered — eminently playable. For these reasons, I think that it is good choice for most experienced players and an excellent pick for those gamers who don’t mind a little record-keeping and who have a keen interest in games dealing with the Napoleonic Wars. Design Characteristics:

Game Components:

Recommended ReadingSee my blog post Book Review of this title which is highly recommended for those readers interested in additional historical background. Recommended ArtworkHere's a Giclee print map of the battle available in various sizes that is great for a Napoleonic themed game room's wall.

TAHGC, SQUAD LEADER, 2nd Ed. (1977)8 comments

SQUAD LEADER is a squad-level simulation of World War II combat. The game was designed by John Hill and published by The Avalon Hill Game Company (TAHGC) in 1977. This subject of this profile is the Second Edition of the game.

INTRODUCTIONWhen it first hit game stores in 1977, SQUAD LEADER — John Hill’s game of World War II small unit combat — rocked the wargaming community as no war game had done since PANZERBLITZ seven years before. Admittedly, the introduction of John Prados’ THIRD REICH in 1974 had created a great deal of buzz within the hobby, but that excitement was nothing compared to the enthusiastic attention that John Hill’s new design received when it first burst on the scene. SQUAD LEADER’s ground-breaking design blended elements of board war games with those of miniatures, but then took this innovative small-unit design architecture to a whole new level. Instead of companies, players now controlled infantry squads, individual support weapons and their crews, and individual vehicles. Not surprisingly, it was an immediate hit with a large segment in the wargaming community and its sales soared. The management at Avalon Hill, realizing that they had a veritable "cash-cow" on their hands, moved to capitalize on this wide-spread enthusiasm by publishing a series of SQUAD LEADER GAMETTES over the next few years, starting with CROSS OF IRON. Each of these follow-up GAMETTES added new rules, new vehicles, additional nationalities, and new map boards to the basic SQUAD LEADER package; however, players still needed to own the original game in order to play them. This steady process of periodic new releases continued for several years. Then, in 1985, the boys in Baltimore broke with this successful retail program and, instead of introducing yet another SQUAD LEADER GAMETTE, launched a completely redesigned, and much more detailed version of the SQUAD LEADER Game System, ADVANCED SQUAD LEADER (ASL). The rest, as they say, is history.DESCRIPTION SQUAD LEADER (2nd Edition) is a small unit, squad-level game of World War II combat on both the Eastern and Western Fronts, 1941-45. One player commands the German forces and the other player controls either Red Army units or American formations. The game is played in turns, and each turn is divided into two player turns: a German and an Allied turn. During each player turn, the phasing (acting) player will perform the following game operations in exactly this order: Rally Phase (during this phase the phasing player will, among other things, attempt to repair malfunctioning AFVs and support weapons, and rally broken units) ; Prep Fire Phase (the phasing player fires on enemy units and conducts several other secondary game operations); Movement Phase (the phasing player moves any units that did not fire during the Prep Fire Phase) ; Defensive Fire Phase; Advancing Fire Phase (moving units fire at half strength); Rout Phase (broken units rout to cover); Advance Phase (the attacking player may advance any still unbroken units one hex into that of the defenders); and the Close Combat Phase (the attacking player conducts all close combat attacks against defending units in the same hexes as attackers). Once this series of player operations is completed, the defending player becomes the phasing player, and the sequence is repeated. At the conclusion of the second player’s turn, the current game turn ends and the turn marker is advanced one space on the Turn Record Track. Fire and movement are important, but morale and leadership are the real keys to John Hill’s vision of small unit combat. Prospective players should take this lesson to heart: units with good morale and excellent leadership almost always have a pronounced advantage over enemy troops with inferior morale — even when those enemy troops have superior numbers and good leaders — whatever the combat situation. SQUAD LEADER (2nd Edition) is a small unit, squad-level game of World War II combat on both the Eastern and Western Fronts, 1941-45. One player commands the German forces and the other player controls either Red Army units or American formations. The game is played in turns, and each turn is divided into two player turns: a German and an Allied turn. During each player turn, the phasing (acting) player will perform the following game operations in exactly this order: Rally Phase (during this phase the phasing player will, among other things, attempt to repair malfunctioning AFVs and support weapons, and rally broken units) ; Prep Fire Phase (the phasing player fires on enemy units and conducts several other secondary game operations); Movement Phase (the phasing player moves any units that did not fire during the Prep Fire Phase) ; Defensive Fire Phase; Advancing Fire Phase (moving units fire at half strength); Rout Phase (broken units rout to cover); Advance Phase (the attacking player may advance any still unbroken units one hex into that of the defenders); and the Close Combat Phase (the attacking player conducts all close combat attacks against defending units in the same hexes as attackers). Once this series of player operations is completed, the defending player becomes the phasing player, and the sequence is repeated. At the conclusion of the second player’s turn, the current game turn ends and the turn marker is advanced one space on the Turn Record Track. Fire and movement are important, but morale and leadership are the real keys to John Hill’s vision of small unit combat. Prospective players should take this lesson to heart: units with good morale and excellent leadership almost always have a pronounced advantage over enemy troops with inferior morale — even when those enemy troops have superior numbers and good leaders — whatever the combat situation.  Not surprisingly, because of the limited scale of the game, units do not possess zones of control, and there are no supply rules. Stacking is limited to four units per hex, only three of which may be squads. Like other modern-era tactical games, SQUAD LEADER — despite the importance it assigns to Close Combat — is primarily a “fire” oriented combat system. For this reason, blocking terrain, concealing terrain, elevation, and line of sight are critical factors in determining which units may fire and be fired on in any given combat phase. Armored Fighting Vehicles are a special case both in stacking and in line of sight (LOS): only one AFV may occupy a hex and, unlike squads which are removed from the map when eliminated, AFVs are inverted to show a wreck counter, and, upon placement, continue to count against stacking and to block LOS through their hex. Finally, because of the tactical detail represented in the game system, SQUAD LEADER (2nd Ed.) offers a variety of specialized rules to cover different combat situations. Thus, there are rules for, among other things: multi-level buildings; smoke; barbed wire; vehicle and equipment malfunctions; mines; entrenchments; fixed fortifications; artillery spotting; off-board artillery support; and even night combat operations. Not surprisingly, because of the limited scale of the game, units do not possess zones of control, and there are no supply rules. Stacking is limited to four units per hex, only three of which may be squads. Like other modern-era tactical games, SQUAD LEADER — despite the importance it assigns to Close Combat — is primarily a “fire” oriented combat system. For this reason, blocking terrain, concealing terrain, elevation, and line of sight are critical factors in determining which units may fire and be fired on in any given combat phase. Armored Fighting Vehicles are a special case both in stacking and in line of sight (LOS): only one AFV may occupy a hex and, unlike squads which are removed from the map when eliminated, AFVs are inverted to show a wreck counter, and, upon placement, continue to count against stacking and to block LOS through their hex. Finally, because of the tactical detail represented in the game system, SQUAD LEADER (2nd Ed.) offers a variety of specialized rules to cover different combat situations. Thus, there are rules for, among other things: multi-level buildings; smoke; barbed wire; vehicle and equipment malfunctions; mines; entrenchments; fixed fortifications; artillery spotting; off-board artillery support; and even night combat operations.  SQUAD LEADER is played using a scenario or “mini-game” format. Six back-printed Scenario Cards are included with the game; these cards provide the specific orders of battle, set-ups, and victory conditions for twelve different East and West Front battlefield situations. Each scenario typically attempts to reproduce a different, but common type of small-unit engagement between German and Russian, and German and American forces during the years 1941-45. SQUAD LEADER is played using a scenario or “mini-game” format. Six back-printed Scenario Cards are included with the game; these cards provide the specific orders of battle, set-ups, and victory conditions for twelve different East and West Front battlefield situations. Each scenario typically attempts to reproduce a different, but common type of small-unit engagement between German and Russian, and German and American forces during the years 1941-45. SQUAD LEADER (2nd Ed.) also offers additional rules for those players who want to experiment further with the game system. There is a subset of “advanced” rules that permit players to design and balance their own scenarios; and there is even a provision for an “extended” SQUAD LEADER campaign that ties multiple scenarios together into one long game A PERSONAL OBSERVATIONFirst, I have a confession: I am, it would seem, just not a SQUAD LEADER kind of guy. I don’t know why, but I personally don’t care much for the SQUAD LEADER Game System. Perhaps it is the small-unit aspect of the game, or maybe I prefer a different level of abstraction when it comes to wargames, but whatever the reason, I just can’t get excited about SQUAD LEADER, ground-breaking tactical design or no. And it has always been so.When the game first appeared in 1977 and most of my regular opponents ran out and immediately bought copies of the new title; I didn’t. The more people raved about the game, the more I stubbornly dug my heels in; when my enthusiastic friends unanimously praised John Hill’s latest creation, I adamantly refused to buy a copy of the new gaming sensation for myself. Perhaps even more frustrating to my long-time opponents was the fact that, not only did I not want to own a copy of the game, I didn’t have any interest in playing it either. Of course, this could only go on for so long. In the final analysis, gaming is very much a quid pro quo type of pastime, so after resisting the imprecations of my friends for months, I finally buckled and bought my own copy of what was, by then, the 2nd Edition of the game. Unfortunately, by the time I did, the first of the SQUAD LEADER GAMETTES, CROSS OF IRON, had already been released, so, at the fevered insistence of my friends, I bought that too. Of course, now that I was stuck for the price of both the game and the GAMETTE, I did what most people would do: I resignedly unwrapped my copy, punched out a number of the counters, and sat down to learn the game system. Three hours later, I had come to two conclusions: first, I had decided that Hill’s tactical combat system was innovative and really quite clever; second, clever or not, I found that my fairly benign lack of interest had turned into an active dislike. I’m not positive, but I think that it was the abstract uniformity of the infantry squads that turned me off the game. Larger units, because of their sheer size and standardized organizations tend to lend themselves fairly easily to abstract quantification. Having personally served in the Army, however, I knew that infantry squads all tended to evidence unique qualities — personalities, if you like — that made each one of them more analogous to an individual athletic team than to some standardized abstract military asset. In the end, the uniformity of the infantry squads and the absolute dependence that the game system placed on differences in leadership just didn’t feel right to me. This is not to say that I didn’t finally play a couple of the short introductory scenarios with a friend (that quid pro quo thing, again), but my heart simply wasn’t in it. Although I am competitive by nature and play wargames to win, in the case of SQUAD LEADER, I just wanted the games to be over with. I genuinely didn’t care who won or lost. For me, that was it; I never opened the game box again until I got ready to sell my old copy on eBay a little while back. So get to the point of all this, already, you say! The moral of this sorry little tale of mine, I suppose, is that when buying games, each player should go with his own gut instinct. If you think that you’ll like a game, you probably will; if you have your doubts, then chances are that you won’t. The fact that I personally don’t like SQUAD LEADER is really quite unimportant. Other players whose opinions I value like the game a lot. And based on the long-term retail sales figures for the game and its many offspring: if I was to hold a convention of all the gamers who share my distaste for the game, I suspect that we could probably all fit into a phone booth. All this puts me in an awkward spot: although I don’t want to play it myself, I still feel obliged to recommend SQUAD LEADER for those players with an interest in a highly-detailed, tactical game system. My rationale for making this recommendation is simple: it has just been far too popular for far too long not to have a lot going for it. The facts, as they say, speak for themselves. Even after thirty-one years, SQUAD LEADER is still a perennial favorite among many experienced gamers and a fixture at most of the major wargaming conventions. In that sense, it has, to put it mildly, aged extremely well. Until the arrival of its perpetually-growing, mutant offspring, ADVANCED SQUAD LEADER, no other title had ever had more articles, rules variations, or scenarios printed in the various hobby magazines than had John Hill’s ground-breaking creation. Today, SQUAD LEADER players occupy an interesting place in the hobby: they are typically players who enjoy the richness of the basic SQUAD LEADER Game System, but who, unlike their ASL brethren, draw the line at permitting a single game to become a virtual way of life. Given my own feelings about the game system, I can’t really say that I blame them. Design Characteristics:

Game Components: