.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

General Dwight Eisenhower with the Paratroopers on the eve of D-Day, June 5, 1944.

Late on the night of 5 June 1944, thousands of Allied paratroops began to parachute into occupied France. Their mission was to seal the approaches to the nearby invasion beaches and to secure safe landing zones for the glider-borne infantry that was scheduled to come in behind them. Within a few hours, the follow-up glider infantry — along with heavy equipment and artillery — began their landings to reinforce the paratroopers who were already on the ground. Because of unexpected cloud cover over the drop zones, however, these airborne units were widely scattered and disorganized during the first hours after the drop. At the same time the gliders were plowing into French fields, waves of Allied planes roared over the Cotentin Peninsula. It was now 0300 on 6 June, D-Day, and flights of Allied bombers had begun to rain thousands of tons of bombs down on the German coastal defenses that bristled along the beaches of the Normandy Peninsula. The initial phases of the most complex military operation in history were finally under way.

Field Marshal Gerd von Runstedt

At 0500 hours, the vast naval armada that had escorted the 150,000 American, British, Canadian, French, and Polish troops who would shortly be landing in occupied France began to shell the German defenses directly behind the beach landing zones. Operation “Overlord,” the amphibious invasion of Hitler’s “Fortress Europe” was about to begin. In the coastal waters off the 7,000 yard wide American landing sector, code-named “Omaha Beach,” the first of many assault teams prepared to come ashore in occupied France. Naval bombardment had commenced almost as soon as the Allied air strikes had stopped. At 0630 hours, 96 specially-equipped amphibious Sherman tanks, the Special Engineer Task Force, and eight companies of assault infantry — four each from the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions — began their invasion run into the target beach.

The Allied plan called for 34,000 men to land in the Omaha Beach sector in the first wave of landings. The second wave was scheduled to begin after 1200 hours and was expected to put another 25,000 men ashore by nightfall. Instead, the landings went wrong almost from the very beginning because of a five mile-per-hour tidal current; virtually every assault group drifted well east of their original objective. American units became hopelessly mingled; finally small ad-hoc teams of thirty to forty soldiers clambered over the seawall and attacked the German positions in the beach draws and on the overlooking bluffs. Gradually, despite heavy German resistance, the American infantrymen pushed inland. But the Allied gains came at a terrible cost; by the end of this first day of the invasion, Omaha Beach had earned the dubious nickname: “Bloody Omaha.” In this one beach sector, over five thousand men would be killed, wounded, or go missing during just the first fourteen hours of D-Day. However, despite heavy casualties, the beachhead would be held and expanded. General Eisenhower’s Great Crusade to liberate Western Europe from Nazi occupation had finally begun.

.DESCRIPTION

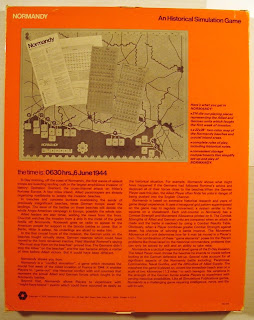

NORMANDY is a grand tactical (battalion/regiment/brigade) level simulation of the fighting that occurred on the beaches and on the fields of France, between the landing Allied forces and the defending Wehrmacht, from 6 through 11 June, 1944. The two-color, hexagonal grid game map covers that part of the Cotentin peninsula over which the contesting armies maneuvered and fought during the six-day time period covered by the game. Each hex is two kilometers from side to side. The game counters represent the actual battalions, regiments, and brigades that either participated, or that could have taken part, in the historical fighting. The simulation is played in game turns, each of which is divided into an Allied and a German player turn. A complete game turn is equal to one day of real time. Each game turn in NORMANDY is asymmetrical and is sequenced as follows (the Allied player always moves first): the Allied First Movement Phase; the three-step Allied Combat Phase (attack allocation segment, offensive ‘naval gunfire’ allocation segment, and combat resolution segment); the Allied Reinforcement Phase; and the Allied Second Movement Phase. The German player turn then proceeds with a similar sequence of player actions: the German First Movement and Reinforcement Phase; the three-step German Combat Phase (attack allocation segment, Allied defensive ‘naval gunfire’ allocation segment, and combat resolution segment); and the German Second Movement Phase. At the conclusion of both player turns, the turn record marker is advanced one space, and the next game turn begins.The actual mechanics of play for NORMANDY, like the other titles in this small SPI family of games, are comparatively simple, but nonetheless interesting. One of this title’s most notable differences from most of SPI’s other early World War II simulations is that all units, not just mechanized units, are allowed to move during the Second Movement Phase. Other game rules are more conventional. Stacking restrictions, for both players, are identical and are determined by terrain: two regiments/brigades, or one regiment/brigade plus two battalions, or three battalions may stack in a non-Bocage hex. Only one regiment/brigade or two battalions, however, may stack in a Bocage hex. Stacking limits apply throughout the entire combat phase, but only at the end of a movement phase. Therefore, there is no penalty to stack or unstack with other friendly units during movement; however, any units forced to retreat because of combat through other friendly units, in excess of legal stacking limits, are eliminated. Combat between adjacent enemy units is voluntary; nonetheless, defending stacks must be attacked as a unitary whole. In contrast, different units in an attacking stack may choose to attack the same or a different adjacent hex, or even to make no attack at all.

Zones of control (ZOCs) are semi-active, but not ‘sticky’. Interestingly, in NORMANDY, all Allied and German units must pay a movement penalty to move adjacent to an enemy unit, but only Allied units are required to pay a penalty to exit an enemy-controlled hex. These ZOC costs vary according to the movement allowance of the phasing unit; for example: all units with a movement allowance of four or less pay one additional movement point to enter an enemy zone of control; all units with a movement allowance of six or more pay three additional movement points to enter an enemy ZOC. All Allied units (only) pay an exit cost of one additional movement point in the first case, and two additional movement points in the second instance. Thus, the ZOC rules in NORMANDY permit a unit with sufficient movement factors to move directly from one enemy ZOC to another. In addition, ZOCs block both supply paths and retreat routes; however, the presence of a friendly unit in the affected hex negates an enemy ZOC for purposes of retreat, but NOT for purposes of tracing supply.

The terrain and movement rules for NORMANDY — except for one significant innovation — are familiar and quite conventional. Variations in terrain are relatively few, and their effects on movement and combat are intuitively logical and hence, are easy to keep track of. Terrain types, in NORMANDY, are limited to eight basic types: clear; Bocage; city; road; fortification; entrenchment; river hexside; and flooded hexside. The movement costs imposed by these different types of hexes vary based on the movement allowance of the phasing unit. For example, units with a movement factor of four or less pay only one movement point to enter clear or Bocage hexes; two additional movement points to cross a river hexside; and four additional movement points to cross a flooded hexside. Units with a movement allowance of six or more pay a single movement point to enter a clear hex; three movement points to enter a Bocage hex; four additional movement points to cross a river hexside; and six additional movement points to cross a flooded hexside. In most cases, a unit may always move one hex, even if accumulated terrain penalties exceed the basic movement allowance of the phasing unit; ‘unsupplied’ armored units, however, are an exception: these units cannot always move a single hex; and, so long as they are unsupplied, must pay regular terrain costs to enter an adjacent hex. Also, the units of both sides — except for German reconnaissance and Allied commando units — may not move out of supply; and if they are placed out of supply by either enemy units or their zones of control, are required to move towards the nearest friendly supply source. Road and city hexes are a special case: all units may move at the rate of 1/3 movement point per hex as long as they are moving along a connecting line of road and/or city hexes.

Terrain effects on combat in NORMANDY always take the form of ‘die roll modifications’ (DRMs). Attacks against enemy units in Bocage, fortifications, and entrenchments require the phasing player to add four to his combat die rolls; while assaults against cities or across river hexsides add three to the attacker’s die roll. Attacks across flooded hexsides are completely prohibited. The special rules governing entrenchments are the most unusual feature of the NORMANDY terrain rules. The combat units of both players, assuming that they have not moved or retreated, may voluntarily attempt to entrench and thereby significantly improve their defensive posture. Regiments and brigades may entrench on a die roll of 1, 2, or 3; battalions may entrench with a die roll of 1 or 2. On any other die roll result, the entrenching units must remain in place, but may try again during the next player turn.

Combat in NORMANDY takes place between adjacent enemy units at the discretion of the phasing player. The outcomes of battles are resolved using a traditional ‘odds differential’ type of Combat Results Table (CRT). As is typical of most of SPI’s World War II games from this period, the CRT is relatively bloodless. In fact, six-to-one or better odds are required before an attack — unaltered by a defensive DRM — has any prospect of producing a Defender Eliminated (DX) result; instead, Exchange (EX) and Retreat (AR and DR) results tend to dominate the CRT’s range of probable outcomes until very high odds are attained by the attacker. Along with his regular ground units, the Allied player also has the use of a limited amount of long-range ‘Naval Gunfire Support’ to augment both his offensive and defensive strength. The Germans have no ‘ranged’ counterpart to Naval Gunfire, but do possess a small number of anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery units; these special combat units, however, may be used for defensive purposes only. The rules affecting armored combat are interesting, if a little frustrating: armored units may not attack at all and have their defense strength halved unless stacked with a non-armored unit; moreover, they may never attack Bocage hexes, whether stacked with a non-armored unit, or not. Another interesting wrinkle in the combat rules, besides the special rules governing the use of armor, harkens back to the early Avalon Hill game, THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE (1965). In a nutshell, the ability of the Allies to conduct offensive battles is restricted for much of the game; thus, while the invading Allies may make an unlimited number of attacks on the first game turn, beginning on turn two, they are restricted to four or fewer attacks per turn. Moreover, any unused Allied attacks may not be saved for use during a subsequent game turn. The German player’s attacks, on the other hand, are unlimited.

B-26 Marauder bomber over Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

The supply rules to NORMANDY impose somewhat different requirements on the two sides. German units are in supply if they are able to trace a supply path of three or fewer hexes to a road that connects via unbroken road hexes of any length to the land portions of all four edges of the game map. For an Allied unit to be in supply, it must be within three hexes of a road that can then follow an unblocked path back to one of the five pre-designated Allied supply areas. In addition, German units that can trace an unblocked route of three hexes or less to a viable map edge (a map edge from which an Allied unit has not exited) are in supply; Allied units occupying supply areas are automatically in supply, even if German units are adjacent. However, if a German unit enters an Allied supply area — even temporarily — it is considered to be destroyed for the remainder of the game. Supply effects for both sides are identical: unsupplied units may not attack and are halved for both movement and defensive combat; ZOCs are unaffected. Only German reconnaissance units and Allied commandos may voluntarily move out of supply; all other units must remain within supply range, if possible; should a unit be placed out of supply by enemy movement or combat, it must move by the most direct path to reestablish its supply line. All Allied units, except paratroops, are automatically in supply on the invasion game turn.

Omaha Beach, American troops landing on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Besides the rules already described, NORMANDY (2nd Edition), also includes a number of special rules cases. For example, most Allied and German regiments and brigades may be broken-down into battalions, and these component battalions may also be recombined to form their parent regiments or brigades. In addition, to reflect the critical importance of shore bombardment during the first days of the battle, the Allied player is allocated eight ‘Naval Gunfire Support’ missions which can be used on each game turn, assuming the targeted units are within range, to increase both the attack and defense strength of Allied ground units. Along with naval support, the Allied player also starts the game with seven operational ‘Paratroop’ units that — if they are to be used in an airborne role — must be dropped on the first turn of the game. It should be noted, however, that paratroop units are automatically eliminated if they scatter onto a German unit and, once dropped, may not move or attack until they have been brought into conventional supply. In addition, as noted previously, both sides may attempt to ‘Entrench’ any units that are designated for this purpose at the end of their player turn, and do not move or retreat during the following game turn. Entrenched units are covered by a blank counter and the contents of an entrenched hex may not be examined until the hex has actually been designated for an attack. Entrenched units may not attack, but do receive a significant defensive bonus because of their entrenched status. Interestingly, this ‘Improved Position’ concept shows up again in David Isby’s SOLDIERS (1972), but really comes into its own as a critically important element for Russian strategic planning in Dunnigan’s WAR IN THE EAST (1974).

Tank belonging to the Panzer Lehr Division, at Normandy, 1944.

To duplicate the imperfect nature of Allied pre-invasion intelligence, the first game turn of NORMANDY imposes a number of special restrictions on the Allied player prior to the start of the game. Before play actually begins, the Allied commander must select his landing beaches, his supply beaches (important both as future supply sources and as entry points for later-arriving reinforcements), and the specific hexes to be targeted by his paratroopers and commandos. These various sites are all written down by the Allied player; only when the Allied player has completed his pre-invasion planning, does the German player set-up his own defending units. Finally, Allied units may not use ‘road movement’ on the first ‘invasion’ game turn.

British Royal Marines landing on D-Day.

The winner of NORMANDY is determined by tallying the total number of ‘victory points’ that the Allied player has accrued by the end of the game. The Allied player receives victory points in two ways: through the capture and uncontested control of certain geographical objectives; and ‘bonus’ victory points depending on the strength of the German Order of Battle actually used in the game. The German player wins by denying the Allied player victory points; the lower the number of Allied victory points, the more advantageous it is for the German player.

Canadian troops landing on Juno Beach, D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Besides simulating the historical battle, NORMANDY also offers five optional scenarios, each of which presents various possible battlefield situations through the use of different German ‘Orders of Battle’ and reinforcement schedules. The Allied Order of Battle and reinforcement schedule, however, always remains the same. Thus, NORMANDY actually provides the players with six different gaming situations; these are: Order of Battle “A” — The Armored Reserve Plan; Order of Battle “B” — the Historical Deployment of German forces; Order of Battle “C” — the Fast Response option; Order of Battle “D” — the Strong Seventh Army option; Order of Battle “E” — the OKW Plan; and Order of Battle “F” — the Rommel Plan. To increase the ‘fog of war’, particularly for the Allied player, the game’s designer recommends that the German player secretly draw one of the six possible Order of Battle options, but hold off revealing his draw until the end of the game. There are no other ‘optional’ rules.

.

A PERSONAL OBSERVATION

Field Marshall Erwin Rommel inspecting the German defenses, Normandy, 1944.The second edition of SPI’s NORMANDY appeared in 1971. It was an upgraded replacement for the original version of the game which had first seen print in 1969. This 2nd edition version of SPI’s first attempt at a D-Day game was an improvement over the first edition mainly because it received some much-needed, additional development work at the hands of John Young, Redmond Simonsen, and the game’s original developer, Bob Champer. Interestingly, the original game started out, like PANZERBLITZ (1970), as one of SPI’s ‘Test Series’ of simulations — in this case, Test Game #6 — and, after its second edition make-over, ended up being published in both a US and a UK (SPUK) version. The primary difference between the two, by the way, was that the UK version had a nicer (colored) game map than its American counterpart.

D-Day, Gold Beach, King Red Sector, Normandy.

.

Not surprisingly, like the rest of the games from the early days of SPI, NORMANDY (2nd Ed.) is, to put it kindly, a little on the plain side. Nonetheless, despite its bland game map and drab counters, NORMANDY introduces a number of interesting ideas that, as already noted, show up in later SPI designs. For players who are used to the KURSK Game System, the dual movement phases of non-mechanized units take a little getting used to; on the whole, however, the design works well enough at simulating many of the critical elements of the battle. One of the game’s main appeals is that it is relatively short and comparatively easy to learn. Another is the game’s built in “fog of war”: the mix of variable German orders of Battle with the requirement that the Allied player commit to his invasion plan before he sees the actual German deployment can make for some very exciting, even hair-raising, game situations.

German prisoners at Utah Beach, D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Where NORMANDY seems to fall down most, in my opinion, is in two important areas: the German Orders of Battle and the supply rules. In the first case, this is particularly noticeable when it comes to the Historical German starting forces. In point of fact, the units defending the beaches arguably are, given the actual record, just a little too weak, both in units and in combat power. So far as the game’s supply rules go: these appear to be both too restrictive and too liberal, depending on which aspect of the rules system one examines. The draconian requirement that — on each and every game turn — units must be rigidly tethered to their supply lines seems, at first blush, to be a little severe. On the other hand, the ability of the Allied player to comingle British, Canadian, and American forces with no restrictions on their supply sources appears to be overgenerous, especially given the significant differences in the logistical requirements of the different national contingents. Interestingly, SPI quickly moved to correct this obvious historical lapse. By the time that Dunnigan's next Normandy game, BREAKOUT & PURSUIT, appeared in 1972, the logistical rules had become a lot more restictive when it came to supplying the different multi-national Allied armies; and when Brad Hessel's COBRA appeared in 1977, the logistical divide between Dempsey's British Second Army, and Bradley's First and Patton's Third American Armies had been made, more-or-less, complete.

Finally, the game procedures governing the actual invasion have been greatly simplified, so players should expect to get very little sense either of the historical drama or the nerve-racking uncertainty of the first few hours of "Overlord." Thus, unlike the real landings, the invasion troops in NORMANDY are always going to come ashore where the Allied player wants them to, and the majority of the Allied amphibious (DD) tanks (unlike their historical counterparts) are not going to be swamped and sunk by the heavy Channel surf.

German reinforced concrete casement, Pointe du Hoc, Normandy, gun removed to escape Allied bombardment.

In the end, I suspect that players will either like or dislike this title based on their taste for simulation detail. Certainly, NORMANDY is readily accessible to almost any type of player, but its relative simplicity and lack of much in the way of historical texture will probably be off-putting to experienced players who are used to denser, more complex game systems. On the other hand, like John Hill’s OVERLORD (1977), it may not be all that complicated, but it still can be both an interesting and exciting game to play. And, perhaps most importantly, unlike virtually every other game that has attempted to simulate the battle for the beaches and hedgerows of Normandy, it doesn’t require a major investment in time to play.

Design Characteristics:

- Time Scale: 24 hours (1 day) per game turn

- Map Scale: 2 kilometers (1.25 miles) per hex

- Unit Size: brigade, regiment, battalion

- Unit Types: armor, reconnaissance, infantry, parachute infantry, glider infantry, commando, anti-tank artillery, anti-aircraft artillery, naval gunfire counters, and information markers

- Number of Players: two

- Complexity: average

- Solitaire Suitability: average

- Average Playing Time: 2½-3 hours

Game Components:

- One 23” x 29” hexagonal Grid Map Sheet (with Allied Invasion Boxes, Paratroop Scatter Diagram, and Turn Record Track incorporated)

- 255 ½” cardboard Counters (the piece count on the box — 214 counters — is incorrect)

- One 5½” x 11¼” map-fold style Set of Rules

- One 8½” x 11” back-printed combined Combat Results Table, Naval Gunfire Chart, and “Designer’s Notes” on the game

- One 8½” x 11” Allied Order of Battle and Appearance Sheet

- One small six-sided Die

- One 8½” x 11” Errata Sheet (August 1973)

- One SPI 12” x 15” x 1” flat card board 24 compartment tombstone-style printed Game Box (with clear plastic compartment tray covers)

Recommended Reading

See my blog post Book Reviews of these titles; both of which are strongly recommended for those readers interested in further historical background.

THE WEST POINT ATLAS OF AMERICAN WARS (Complete 2-Volume Set)

0 comments:

Post a Comment